Kim Scott is the author of Radical Candor: Be a Kick-Ass Boss Without Losing Your Humanity and Radical…

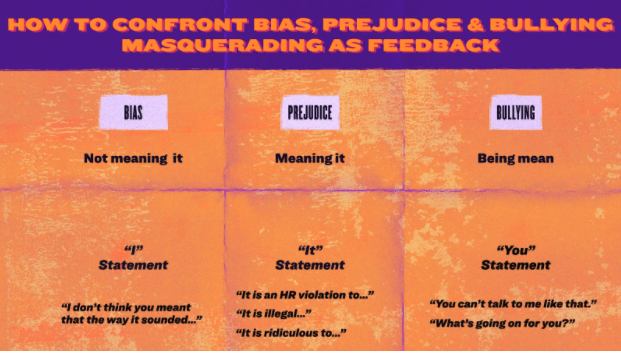

3 Ways to Confront Bias, Prejudice & Bullying Masquerading as Feedback

One of the things that I had to confront when I wrote the follow-up to Radical Candor, Radical Respect, is that bias, prejudice and bullying often masquerade as feedback. None of this is legitimate feedback, or, as I like to call it, guidance — praise and criticism that shows you care about the person while also challenging them directly. What follows are some thoughts about how to challenge bias, prejudice and bullying.

But let me say that it shouldn’t be all on you, the target, to respond to them. There are things leaders and upstanders can do too. But this article is for people who are being targeted.

What’s the difference between bias, prejudice, and bullying? Too often we conflate the three. Here are some quick definitions. Bias is “not meaning it.” It’s often unconscious. Prejudice is “meaning it.” It’s a conscious belief. And Bullying is “being mean.”

If you want to demonstrate that you are open to legitimate feedback, you can look for the 5-10% of whatever was said that you CAN agree with and give voice to that. And if you’re too angry in the moment to talk, feel free to say, “as for the rest of what you’ve said, I’d like to think about it, and get back to you. Then do get back to them when you’ve had a chance to think more deeply about what they’ve said.

RESPONDING TO BIAS: USE AN “I” STATEMENT TO INVITE THE PERSON TO UNDERSTAND THINGS FROM YOUR PERSPECTIVE

If it is bias you’re confronting, you may choose to help the person notice the mistake. It’s not your job to educate the person who just harmed you. But you may choose to do the work because saying something may cost you less emotionally than remaining silent. If that’s the case, you’re not calling the person out; you’re inviting the person in to understand your perspective. Easier said than done. Even if you don’t know what to say, start with the word “I.”

Starting with the word “I” invites the person to consider things from your point of view—why what they said or did seemed biased to you. The easiest “I” statement is the simple factual correction. For example, “I don’t think you’re taking me seriously when you call me honey.”

An “I” statement can let a colleague know you have been harmed without being antagonistic or judgmental. For example, “I don’t think you meant to imply what I heard; I’d like to tell you how it sounded to me …” An “I” statement can be clear about the harm done while also inviting your colleague to perceive things the way you do or to realize that an incorrect assumption was made.

An “I” statement is a generous response to someone else’s unconscious bias. It may be more emotionally satisfying to say, “Don’t you realize what a pig you’re being when you say that?” But shaming is an ineffective strategy. When a person feels attacked or labeled (e.g., “They’re calling me a sexist/racist/homophobic/other label”), it’s much harder for the person to be open to your feedback.

Another benefit of an “I” statement is that it’s a good way to figure out where the other person is coming from. If people respond politely or apologetically, it will confirm your diagnosis of unconscious bias. If they double down or go on the attack, then you’ll know you’re dealing with prejudice or bullying.

What if you’re not sure it’s bias? It’s OK. You don’t have to be 100% sure to speak up. Whether you’re right or wrong, your feedback is a gift. When you speak up, remain open to the possibility that you’re It can be useful to be more explicit about what just happened.

“I think you confused me with someone who looks like me to you.” If you have the kind of relationship and humor that makes it comfortable, you can make a small joke. “Sam is the other woman/person of color on the team. I am Alex” or “I think it was bias that caused you to put me into the same bucket as Sam.”

Growing up, one of my close friends was a Korean-American girl in my class at school. When I once called her by the name of another Korean-American girl at our school, she said to me, “I bet you think she and I look alike. When my father moved here, he thought all white people looked alike, just like you think all Koreans look alike.” Her remark gave us an opportunity to have a real conversation about this sort of biased conflation. It was embarrassing to talk about but would have been more embarrassing not to talk about.

Responding to bias with an “I” statement has a number of benefits. I am not trying to “should” all over you. I’m not saying you “should” speak up. But many of us are more acutely aware of the downsides than the upsides of responding. It can be helpful to think through the pros since we feel the cons in our gut.

First, by speaking up, you are affirming yourself. Every time someone says something that bothers you and you ignore it, a tiny feeling of helplessness creeps in. Every time you respond, your sense of agency is strengthened. Ashley Judd put it well on a recent episode of Adam Grant’s WorkLife podcast. “Fear comes from focusing on the costs of speaking up. Courage comes from focusing on the costs of staying silent.”

Second, you are interrupting the bias that is harming you, and you may even persuade the offender to change their behavior, which will improve things not only for you but for others.

Third, by speaking up clearly and kindly, you will be supporting the notion that doing so is acceptable behavior, encouraging others to do the same. Doing this often establishes that having one’s bias confronted does not make one irredeemably bad, thus making others more comfortable pointing out bias when they notice it. This is how norms—standards of social behavior—are established. When we ignore bias, we allow it to be repeated and reinforced.

Fourth, your relationship with your colleague may improve thanks to your intervention. It is easier to get along with someone who isn’t doing something that pisses you off over and over.

Fifth, you are doing the person who is saying the biased thing a favor. If they don’t consciously mean what they are saying, when you point it out, you give them an opportunity to stop making that mistake.

Often corporate feedback training will advise you to respond by saying, “When you do X, it makes me feel Y.” But I don’t recommend this approach when confronting bias at work. In these situations, you don’t want to give anyone else the power to “make” you feel anything.

Furthermore, you don’t want to fuel the “She’s overly sensitive” or “He’s always angry” flames of bias. You want to correct the bias, get the facts as you understand them on the table, and show the harm done.

RESPONDING TO PREJUDICE: USE AN “IT” STATEMENT

What do you say when people consciously believe that the stereotypes they are spouting off about are true—when you are confronting active prejudice rather than unconscious bias?

It’s hard to respond to bias, but it’s much harder to respond when people believe that your gender, race, religion, sexual orientation, gender identity, socioeconomic background, or any other personal attribute makes you incapable or inferior in some way.

One, if you’re like me, prejudice makes you madder than bias. I am way more pissed off when someone asserts that it’s been scientifically proven that women are biologically programmed to be this or that than I am when someone makes a remark that reveals some unconscious bias. Anger can make it harder to respond—especially for people who are not “allowed” to show anger as a result of bias. It’s bias piled on top of prejudice.

Two, you’re probably less optimistic that a confrontation will result in change when it’s prejudice rather than bias that you’re dealing with. People won’t apologize for their prejudiced beliefs just because you point them out; they know what they think. So why bother discussing it? The reason to confront prejudice is to draw a bright line between that person’s right to believe whatever they want and your right not to have that belief imposed upon you.

Using an “It” statement is an effective way to demarcate this boundary. One type of “It” statement appeals to human decency: “It is disrespectful/cruel/et cetera to …” For example, “It is disrespectful to call a grown woman a girl.”

Another approach references the policies or a code of conduct at your company: For example, “It is a violation of our company policy to hang a Confederate flag above your desk. It invokes slavery and will harm our team’s ability to collaborate.” The third invokes the law: For example, “It is illegal to refuse to hire women.”

RESPONDING TO BULLYING: USE A “YOU” STATEMENT TO CREATE CONSEQUENCES

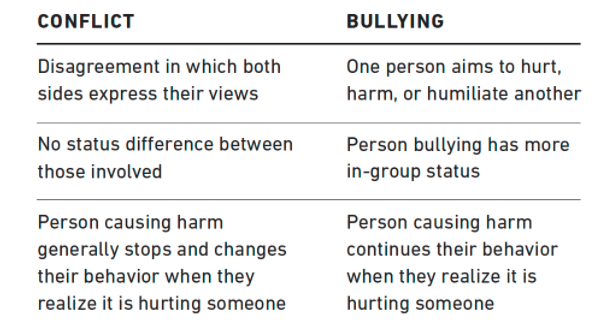

What is the difference between bullying and conflict? Here’s a simple way to think about it, adapted from the work of PACER, a nonprofit that leads a bullying prevention center.

A bully is often emboldened by some sort of illegitimate status. I use the words “in-group status” (e.g., being white when the majority of leaders are white, or having a degree from a university that is particularly respected at the company), not “power,” deliberately here. When I talk about bullying, I’m talking about behavior between people who don’t have positional power over one another. Once positional power enters the equation, bullying becomes harassment.

When someone is bullying you, their goal is to harm you. If they are trying to hurt you, telling them they succeeded may embolden them to double down since they know they are succeeding. Ignoring bullies doesn’t work, either. The only way to stop bullying is to create negative consequences for the person doing the bullying. Only when bullying stops giving them some sort of advantage will bullies alter their behavior. When you’re the victim of bullying, though, you often feel powerless to stop it.

One way to push back is to confront the person with a “You” statement, as in “What’s going on for you here?” or “You need to stop talking to me that way.” A “You” statement is a decisive action, and it can be surprisingly effective in changing the dynamic. That’s because the bully is trying to put you in a submissive role, to demand that you answer the questions to shine a scrutinizing spotlight on you. When you reply with a “You” statement, you are now taking a more active role, asking them to answer the questions, shining a scrutinizing spotlight on them.

An “I” statement invites the person to consider your perspective; an “It” statement establishes a clear boundary beyond which the other person should not go. With a “You” statement, you are talking about the bully, not yourself. People can let your statement lie or defend themselves against it, but they are playing defense rather than offense in either case.

I don’t relish conflict, so “You” statements don’t come naturally. My impulse, when someone harms me, is to let that person know how the behavior made me feel. It was my daughter who first pointed out to me that showing that kind of vulnerability when you are being bullied is counterproductive.

She had come home one day from school upset that a kid I’ll call Austin was giving her a hard time on the playground. I advised her to give Austin the benefit of the doubt, to say something along the lines of, “When you knock my lunch off the table, I get really hungry, and it hurts my feelings.” That got me a big eye roll. Her teacher had made a recommendation along the same lines.

“What is wrong with adults?” my daughter wanted to know. “Why don’t you get it? Austin is trying to hurt my feelings! If I say, ‘What you did hurt my feelings,’ it’s like saying, ‘Good job, Austin, mission accomplished, you did what you wanted to do.’ It’s like giving Austin a cookie for being mean to me!” My daughter was absolutely correct.

When someone gives you “feedback” that is not in fact feedback at all but instead is bias, prejudice or bullying, it’s hard to know how to respond without seeming to be shut down to feedback, or defensive. I hope these suggestions help you push back in a way that minimizes the harm done to you, and perhaps prevents it from happening again or even improves your relationship with the person.

And I hope that it leaves you open to feedback that is truly helpful in the future. One of the many ways in which bias, prejudice and bullying harm our ability to grow in our career is that when we get too much bias, prejudice and bullying masquerading as feedback, it’s hard to hear legitimate feedback when we get it.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

- Take the Radical Candor quiz >>

- Sign up for our Radical Candor email newsletter >>

- Listen to the Radical Candor podcast >>

- Shop the Radical Candor store >>

- Get the “Radical” books >>

- Get Radical Candor coaching and consulting for your team >>

- Get Radical Candor coaching and consulting for your company >>

Need help practicing Radical Candor? Then you need The Feedback Loop (think Groundhog Day meets The Office), a 5-episode workplace comedy series starring David Alan Grier that brings to life Radical Candor’s simple framework for navigating candid conversations.

You’ll get an hour of hilarious content about a team whose feedback fails are costing them business; improv-inspired exercises to teach everyone the skills they need to work better together, and after-episode action plans you can put into practice immediately to up your helpful feedback EQ.

We’re offering Radical Candor readers 10% off the self-paced e-course. Follow this link and enter the promo code FEEDBACK at checkout.