Kim Scott is the author of Radical Candor: Be a Kick-Ass Boss Without Losing Your Humanity and Radical…

6 Steps to Successfully Debating (Not Killing) Ideas

*This article about debating ideas is part of our new series about the Get Stuff Done (GSD) Wheel and has been excerpted from Radical Candor: Be a Kickass Boss Without Losing Your Humanity.

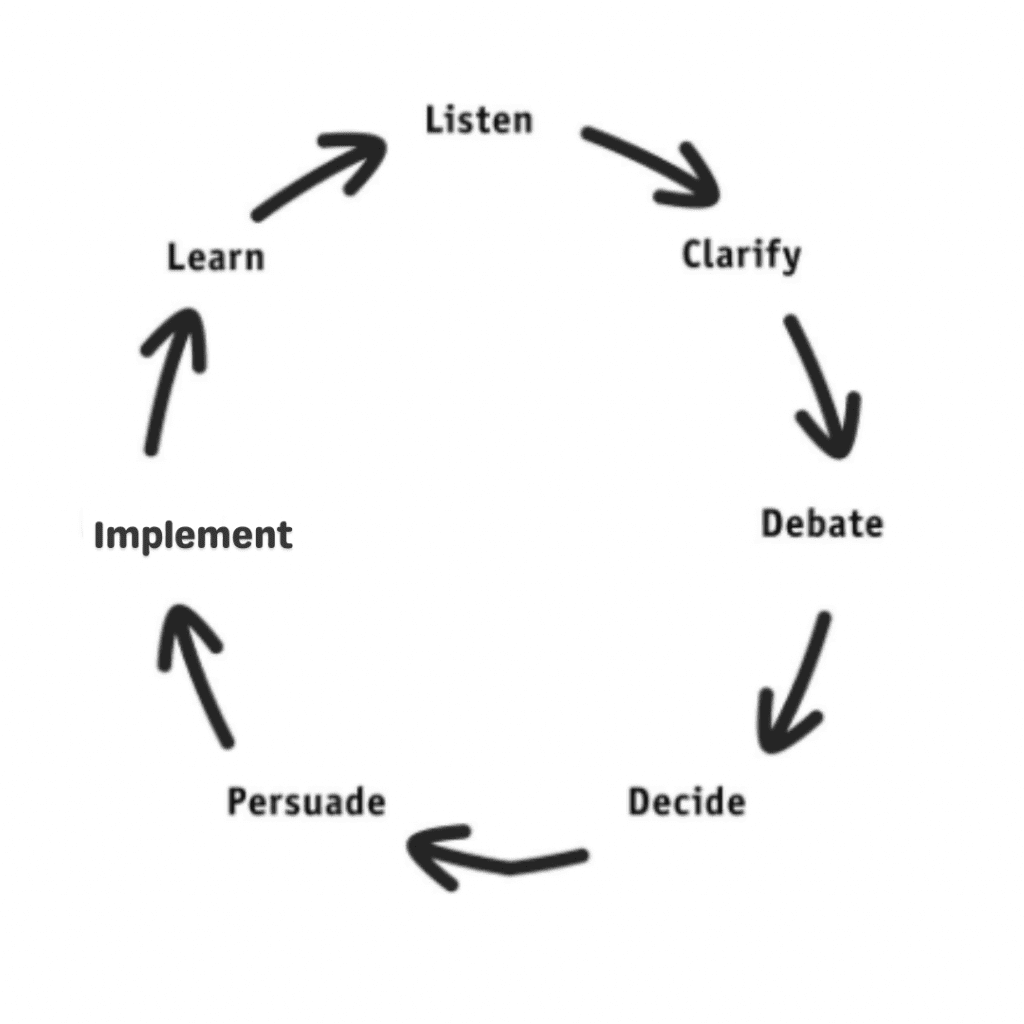

Once you’ve spent all that time listening to and clarifying an idea — getting it really clear in your own mind and making it easy for others to understand — it’s tempting to feel like you’re done. Not so fast! The point of spending all that time in clarification mode was just to get the idea ready for a debate.

If you skip the debate phase, you’ll make worse decisions, you’ll be unable to persuade everyone who needs to implement, and you’ll ultimately slow down or grind to a halt.

Once again, you as the manager don’t have to be in every debate — in fact, you shouldn’t be. But you’ve got to make sure that they happen, and that there is a culture of debate on your team.

Listen to the Debate Meeting podcast episode >>

When Steve Jobs was a kid, his neighbor showed him a rock tumbler — a can that spun on a motor. The neighbor asked Steve to gather up some ordinary rocks from the yard. He took the stones, threw them into the can, added some grit, turned on the motor, and, over the racket, asked Steve to come back two days later.

When Steve returned to the noisy clatter of the garage, the neighbor turned off the contraption and Steve was astounded to see how the ordinary rocks had become beautiful polished stones. Steve would later say that when a team debated, both the ideas and the people came out more beautiful — results well worth all the friction and noise.

Your job as a boss is to turn on that “rock tumbler.” Too many bosses think their role is to turn it off — to avoid all the friction by simply making a decision and sparing the team the pain of debate. It’s not. Debating takes time and requires emotional energy. But lack of debate saps a team of more time and emotional energy in the long run.

Of course, it’s also possible to leave the rock tumbler on too long, leaving nothing in the can but some dust. Here are some ideas that can help you keep the debate going without grinding everyone down too much.

1. Keep debating focused on ideas, not egos

Make sure that individual egos and self-interest don’t get in the way of an objective quest for the best answer. Nothing is a bigger time-sucker or blocker to getting it right than ego. On a broad level, this means intervening when you start to sense that people are thinking, “I’m going to win this argument,” or “my idea versus your idea,” or “my recommendation versus your recommendation,” or “my team feels . . .”

Redirect them to focus on the facts; don’t allow people to attribute ownership to ideas, and don’t get hijacked by how others who aren’t in the room might (or might not) feel.

Remind people what the goal is: to get to the best answer, as a team. You’re creating a collaboration of great minds, not monitoring a high school debate competition or running a presidential election.

If you have to, set ground rules at the beginning of the meeting, or — if your team would find it amusing and useful rather than ridiculous — put a prop like an “ego coat check” outside the door.

Another way to help people search for the best answer instead of seeking ego validation is to make them switch roles. If a person has been arguing for A, ask them to start arguing for B. If a debate is likely to go on for some time, warn people in advance that you’re going to ask them to switch roles.

When people know that they will be asked to argue another person’s point, they will naturally listen more attentively.

2. Create an obligation to dissent

I once interned at McKinsey for a summer, and what impressed me most about the company was its ability to spur productive debate. How did they do it? McKinsey had very consciously created an “obligation to dissent.” If everyone around the table agreed, that was a red flag.

Somebody had to take up the dissenting voice. McKinsey alums often brought this with them into the companies they later worked for. One ex-McKinsey executive at Apple struggled to foster a culture of debate on a team he inherited in Japan.

He had a bunch of gavels made up with “duty to dissent” written in Japanese on them. If there wasn’t a robust enough argument in a meeting, he’d slide the gavel across the table to someone, as a sign to take up the opposite point of view. This simple prop was surprisingly effective.

Get your Radical Candor 'Duty to Dissent' swag: mugs, ping-pong paddles and stickers.

3. Pause for emotion/exhaustion

There are times when people are just too tired, burnt out, or emotionally charged up to engage in productive debate. It’s crucial to be aware of these moments because they rarely lead to good outcomes. Your job is to intervene and call a time-out.

If you don’t, people will make a decision so that they can go home; or worse, a huge fight stemming from raw emotions will break out.

If you’ve gotten to know each person on your team well enough, you’ll be sufficiently aware of everyone’s emotions and energies so that you’ll know when it’s necessary to step in and defer the debate until people are in a better frame of mind.

4. Use humor and have fun

The spirit with which a debate is launched often determines the tenor of what follows. I have found that people on a team I lead key off my mood to an almost alarming extent; when I find a way to have fun with a debate, others often follow suit.

In some cases, it might be simple humor or opening the meeting with a good self-effacing story. What you say is less important than the tone it conveys, and the mood it sets for what follows.

Finally, it’s important to be aware that not everyone enjoys debate. Some people find the very act of debate aggressive and/or threatening. I recall a time when we were developing a class at Apple on communication, and I described my ideas on creating a positive space for debate.

Suddenly a colleague next to me smiled and burst out, “Oh! You have been debating with me all this time just to make the class better. I thought you were just trying to drive me crazy.”

What to me had been an exciting opportunity to push each other to hone and develop ideas had been to him an excruciating exercise in one-upmanship.

This drove home the importance of providing a clear explanation up front about the purpose of debate and creating a positive space in which it can occur — not to mention the importance of knowing the people I was debating with well enough to recognize when I was driving them nuts without meaning to!

5. Be clear when the debating will end

One of the reasons that people find debate stressful or annoying is that often half the room expects a decision at the end of the meeting and the other half wants to keep arguing in a follow-up meeting.

One way to avoid this tension is to separate debate meetings and decision meetings. Another way to ease the anxiety of the people who want to know when the decision will get made is to have a “decide by” date next to each item being debated.

Then at least they know when the debate will end and the decision will be made. I recommend setting up a weekly “big debate” meeting.

In my staff meeting we identified the most important debate each week, and who needed to be involved (see “ ‘Big Debate’ Meetings” in chapter 8).

6. Don’t grab a decision just because debating has gotten painful

It’s tempting to end debates and make a decision too soon when a debate becomes too painful. You might be creeping up on a topic that’s been a subject of great contention.

At times like this, people often look to the boss to end the suffering and make a decision. My instinct is to be a peacemaker or to get to a decision quickly. But a boss’s job is often to keep the debate going rather than to resolve it with a decision.

It’s the debates at work that help individuals grow and help the team work better collectively to come up with the best answer.

I once made a preemptive decision about what seemed like a small thing — a seating chart — that ended badly. We didn’t even have cubes, just tables. As the team grew from 10 to 65 people, we eventually had to rearrange the space and move everyone’s desk.

Everybody had an opinion about what the layout should be, and a young project manager volunteered to herd the cats. They were hard to herd. The angst about who sat next to whom and how far they were from a window went on for the better part of a week.

Frustrated, I came in on a Sunday and moved everyone’s desks myself. The result was near mutiny on Monday morning. “We were this close to a decision!” exclaimed the project manager. “And you just set us back a week.” He was an unusually levelheaded person, but there were tears of real frustration in his eyes.

The right thing to do would have been to set a “decide by” date, so everybody would know that they couldn’t lobby the project manager endlessly. If the debate seemed too rancorous, I could have asked him how I could help.

For example, I could have suggested the people whose differences he was having a hard time reconciling try to wrap it up over a meal or a walk, or that they switch roles and argue for each other’s positions.

But grabbing the decision away from him and making it myself was not only overbearing; it simply didn’t work.

This post has been excerpted from Radical Candor: Be a Kickass Boss Without Losing Your Humanity (get bulk book discounts for teams!). Learn more about the GSD Wheel in chapter 4 of Radical Candor and download our reading guide to test your knowledge of the concepts as you go. Check back soon for the next step in the GSD wheel, Decide. (Read the previous post about clarifying ideas >>)

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Sign up for our Radical Candor email newsletter >>

Shop the Radial Candor store >>

Need help practicing Radical Candor? Then you need The Feedback Loop (think Groundhog Day meets The Office), a 5-episode workplace comedy series starring David Alan Grier that brings to life Radical Candor’s simple framework for navigating candid conversations.

You’ll get an hour of hilarious content about a team whose feedback fails are costing them business; improv-inspired exercises to teach everyone the skills they need to work better together, and after-episode action plans you can put into practice immediately to up your helpful feedback EQ.

We’re offering Radical Candor readers 10% off the self-paced e-course. Follow this link and enter the promo code FEEDBACK at checkout.