By Gaurav Sharma, founder and CEO of Attrock, a results-driven digital marketing company he grew…

4 Ways to Help New Managers Succeed

I’ve had a 22-year operational management career, and naturally, I’ve had a lot of new managers in my organizations over the years. ‘New managers,’ in this case, means ‘new-to-management’ not so much ‘new-to-me’ or ‘new-to-the-org.’ I’m talking specifically about people new to the practice of management. Oh yeah, I was also a new manager once, many moons ago as a young Lieutenant in the US Marines.

So I really understand the struggles and challenges of being a new manager.

“Ask any new manager about the early days of being a boss—indeed, ask any senior executive to recall how he or she felt as a new manager. If you get an honest answer, you’ll hear a tale of disorientation and, for some, overwhelming confusion.”

From Becoming the Boss by Linda Hill, Harvard Business Review, 2007

One day, you’re an individual contributor, and likely, you’re a successful one because that is what typically earns you the opportunity to become a manager. Suddenly you’re promoted or get a new job as a manager. That’s great! The thing is, though, that what got you here with success, won’t get you continued success as a manager. I mean this quite literally.

The activities that led to success as an individual contributor LOOK NOTHING LIKE the activities that will lead to success as a manager.

They do not resemble one another at all. No hyperbole.

But despite this, new managers receive very little coaching on how to be successful in their new role.

“And as I neared the end of my corporate days, I realized I’d received much more management training in the last five years than I did in the first 20 years — when I really needed it — combined.”

From Why Do We Spend So Much Developing Senior Leaders and So Little Training New Managers? by Victor Lipman, Harvard Business Review, 2016

As I’ve talked to 100s of people, the single most common concerns raised by senior leaders and HR pros alike has been “We have a ‘new manager’ problem that we badly need help with.” These companies are often communicating huge front line employee engagement issues related to the performance of their middle and entry level of management. This isn’t a huge surprise. Companies often invest extraordinary sums of money to have famous authors come in to distribute brain candy and consultants to build cohesive senior executive teams. But in so many of the companies I’ve seen, the investment level in training new and middle level managers is not remotely close.

The theory of senior level investment, according to Lipman, has to do with the leverage exerted upon the organization by a relatively small number of leaders. One C-Level person has massive impact on an org. Gotta fix that guy! That gal needs to improve! It is also often the case, though, that the front line and middle layer managers, in aggregate, have at least as much leverage on the organization and directly results in costly turnover and ineffective performance.

I think this problem is enormous and and not close to resolved. To get our own conversation going, here are some of the key areas I’ve seen new managers routinely struggle with:

- Giving feedback

- Helping their team grow

- Driving team results

- Formal performance management

Here are some ideas for how manager-focused L&D (Learning and Development) and senior executives can better mentor new managers in these areas.

1. Teach New Managers to Be More Than Cheerleaders

When it comes to giving feedback to their teams, new managers spend so much time in Ruinous Empathy that they should have to pay rent to Ruinous Empathy. They become cheerleaders, with refrains of “Go Team!” and “We are mighty”, almost complete with pom-poms. Like cheerleaders, new managers aren’t yelling, “R-U-N play-action more because that is the best way to exploit their over-aggressive linebackers!”

New managers perhaps don’t feel like they have the cachet or capital to challenge their teams too directly. Perhaps the new manager is trying logically to avoid micromanagement. It could also be that the new manager is flat-out conflict averse and struggles to issue a direct challenge no matter how justified. Indeed, it is human nature that the more difficult the conversation, the less clear we become. In either case, the manager is doing the individual and the remainder of the team a disservice by not clearly articulating performance problems.

New managers also become cheerleaders with their praise. They offer non-specific praise such as “Great job!” intended to make friends and to make people feel good. Often, the new manager is far too concerned with being liked versus being respected or competent. It’s normal to want to be liked. The manager’s job, of course, is to help the team be more successful and being liked may very well not fit into that plan.

We can help new managers avoid these natural tendencies by teaching them what good feedback looks like. An easy first step is to have them watch our Radical Candor video, listen to Kim’s First Round talk, and read some of the feedback articles on our site.

They’ll learn that when things aren’t going as well as hoped, they should “Just say it!” They’ll learn that giving criticism that is kind and clear is far more helpful than not saying it at all.

It’s also important for new managers to learn that showing you Care Personally does not simply mean to give more praise — praise is not the way to turn all direct challenges into Radical Candor. Managers should avoid the feedback sandwich – putting a piece of praise around a tough message – for two reasons. First, the praise is usually meaningless – very general, not particularly sincere. Second, and much more importantly, leading with praise in delivering a tough message confuses and dilutes the tough message.

When it comes to giving praise, new managers need to learn how to be more impactful. For example, when they give specific praise – praise that includes a clear articulation of what was achieved and why that achievement matters — they can help people to see and feel what success looks like in the organization. The Positive Coaching Alliance teaches us that “positive is powerful,” but are careful to say that generic, non-specific praise is just as useless for little kids as it is for adults. I’ve found similar results in the organizations I’ve run and in the little league teams I’ve coached.

We can also help new managers learn that more often than not, their team will actually prefer getting direct challenges. By providing a way for team members to gauge new managers’ feedback, they’ll get a strong message as to whether people think they’re pulling their punches.

2. Help New Managers Enable Their People’s Futures

New Managers tend to really struggle with helping their team grow because they are generally not taught how to have Career Conversations.

Great managers help bring some intentionality, structure, and accountability to the process of career planning for their people, by understanding the employee’s past and future, which then enables the employee to take relevant action right now.

You can help new managers, and their teams, simply by providing basic training on Career Conversations. We’ll be bringing a bunch more content soon about the details of how to have good Career Conversations, so watch this space for additional resources.

3. Guide New Managers in Setting Expectations for and Driving Performance

Many new managers find themselves in difficult performance management situations because they haven’t clearly articulated standards for performance and they don’t always follow a sound process for delivering results. It’s difficult for the team to succeed if they don’t know what the expectations are.

Help new managers set expectations by coaching them on how to set goals – or OKRs – in collaboration with team members. OKR means Objectives and Key Results. In case you’re not totally familiar, Betterworks does a nice job defining OKR basics here.

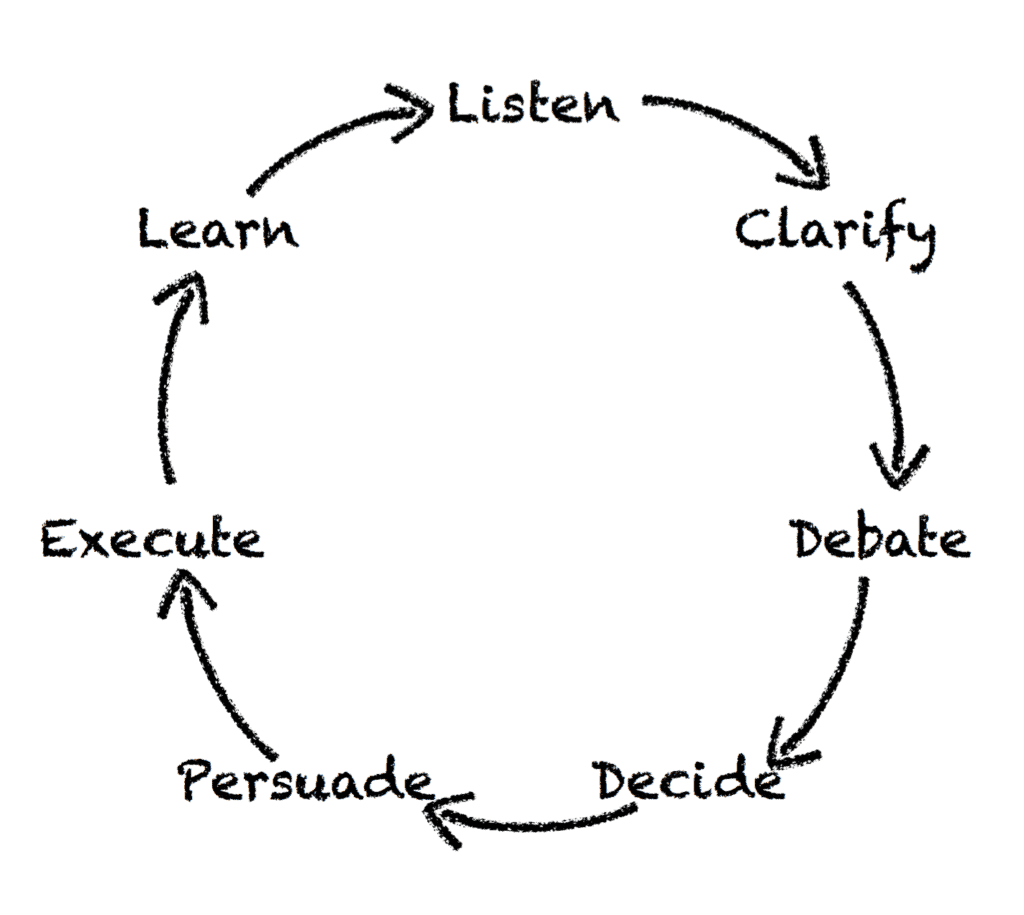

Driving results is hard. We’ve developed a process for helping drive better results more consistently. This process is a loop and operates conceptually like Boyd’s Cycle.

Listen

Your team should know what the company is trying to achieve, and they likely have some of the best ideas for what your team should be achieving. First, listen to their ideas in trying to figure out what results your team should be pursuing.

Clarify

Remember that new ideas are fragile and therefore easily squished. A critical role a manager can play is to augment the voice of their team by helping the team clarify their ideas and by clarifying the manager’s own understanding of the ideas.

Debate

Allowing the team time and space to publicly debate the ideas is a critical step. Guidelines for good debate include making the discussion about the ideas and not about egos. It’s about finding the best answer together, not about who won the debate.

Decide

The manager doesn’t always need to decide, but the manager needs to make certain that the decider is clearly identified and that a decision gets made. If there are any follow up items or other process points, such as specific stakeholder checkins, for making a decision, the manager needs to make sure those are articulated.

Persuade

Not everyone required to achieve results will have been involved in each step of this process. That’s ok, but those people need to be brought along after the decision is made.

Execute

Now it’s go time. Time to stop talking and start working. One of the great benefits of carefully abiding by the preceding process is that now the team can execute with great autonomy and purpose with buy-in and understanding.

Learn

Your team’s execution changes the context and uncovers new variables. The new context needs to be observed and understood and then used to feed the process again. Your team will have the best information; time to listen and go around the wheel again.

This is hard work, and in leading a team, managers should try to execute this cycle quickly but thoroughly to improve their ability to drive results. L&D can help new managers learn and understand this process by providing training resources and ongoing support. Watch this space for resources you can use to teach our “Get Stuff Done” results wheel!

4. Encourage New Managers to Utilize Formal Performance Management

I’ve seen this scenario far too often: The new manager sticks their neck out for an obvious under performer. They think they can coach everyone out of the problem. They think, because they were successful as an individual contributor, they can coach anyone out of a performance funk.

Of course, coaching is the right first step. It’s a great start. Good performance-related coaching includes a clear expectation for improvement and a clear timeline for improvement. I recommend that a manager start here and then re-assess the performance gap.

The problem arises as the coaching doesn’t take. After one or two cycles of accountable performance coaching, it’s time to move to a more formal process. The recommendation might sound aggressive, but I don’t think so, for a couple reasons:

- The new manager often struggles to identify that breaking point (when to move to a formal process) on their own. Even if they are able to identify when it’s time for more aggressive action, a concern about being wrong about their coaching often prevents them from acting. Beyond that, many organizations starve young managers of critical support from Human Resources Business Partners (HRBPs), who could help the manager find their footing and get control of the performance management problem. Without this support, a formal management process is the best way for new managers to navigate these difficult situations.

- I believe deeply that the formal Performance Improvement Plan (PIP) is a gift of clarity for the under-performer. It serves to clarify in writing the specific performance issues in a way that all critical stakeholders can understand – most importantly, the person struggling with performance. This answer is obvious when written at a distance and in theory in a blog post. But new managers often resist PIPs because of an excessive focus on the last line, which is often something like “failure to comply within 60 days will result in termination.” This line is more of a “cover-your-butt” tool to fire someone; using PIPs solely for this purpose is a huge miss. The rest of the document should be viewed as a great clarifying exercise. If you believe the harder the conversation, the less clear you are, then clarifying performance gaps and success criteria via a PIP is the greatest gift any manager – and especially a new one – can give a struggling team member.

L&D and senior executives can and should ensure that new managers know when and how to make use of formal performance management processes in their organization.

Does your company have any great training programs for new managers? What other areas have you seen present challenges for new managers?

Need more help as a new manager learning how to get stuff done? Then you need The Feedback Loop (think Groundhog Day meets The Office), a 5-episode workplace comedy series starring David Alan Grier that brings to life Radical Candor’s simple framework for navigating candid conversations.

You’ll get an hour of hilarious content about a team whose feedback fails are costing them business; improv-inspired exercises to teach everyone the skills they need to work better together; and after-episode action plans you can put into practice immediately to up your helpful feedback EQ.

We’re offering Radical Candor readers 10% off the self-paced e-course. Follow this link and enter the promo code FEEDBACK at checkout.

Want more tips? Sign up for our email newsletter >>

*This article was updated Sept. 9, 2020