This post about how to fix communications issues in the workplace is by Zachary Amos,…

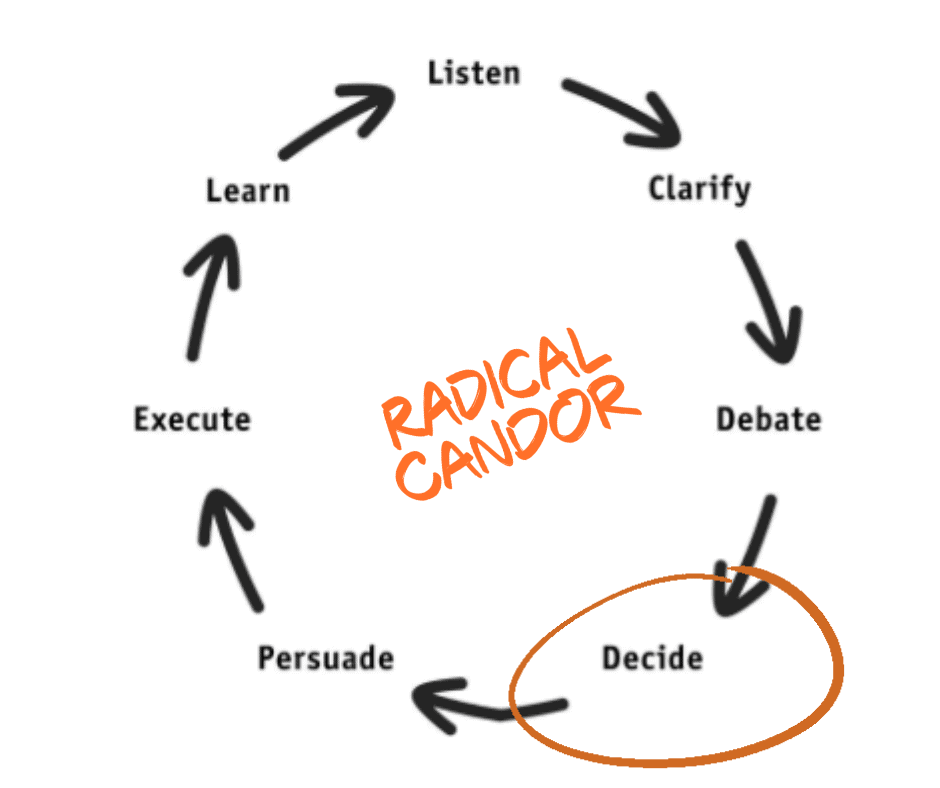

4 Things to Consider When Making Decisions to Get Shit Done

*This article about making decisions is part of our new series about the Get Stuff Done (GSD) Wheel and has been excerpted from Radical Candor: Be a Kickass Boss Without Losing Your Humanity.

Once you have gone through the listening, clarifying and debating spokes of the Get Stuff Done Wheel, you have likely lined up decisions and facts and (hopefully) shoved all ego — especially your own — out of the way.

Now is the time, as Twitter and Square CEO Jack Dorsey put it, to “push the decisions into the facts.” Here is what I’ve learned about what that means — how to help a team make the best possible decisions — or to “always get it right.”

1. When Making Decisions, You’re not the decider (usually)

I once had an impromptu conversation with a woman on one of my teams. At lunch one day, I asked her how it was going. She rocked back and forth, clutching her head.

“What’s wrong?” I asked, alarmed.

“I thought I was hired for my brain, but I have not been allowed to use it a single time since I got here! But Mark” — and here she winced visibly at uttering her manager’s name — “makes all the decisions, even when he doesn’t really understand the situation.”

I attended Mark’s next staff meeting, at which he was reviewing the team’s quarterly OKRs (objectives and key results).

As he flashed up the first slide, I felt optimistic. I had taken the job only three weeks before so I didn’t know much, but his plan looked great. The deck he’d built to explain the goals for the quarter had everything I looked for: objectives that were clear and ambitious, key results that were measurable.

Then I saw that the person sitting to my right was slouching a little in her chair. Looking around the room, I registered arms crossed, faces stony, and a silence so loud that it penetrated even Mark’s well-prepared speech.

Mark’s response was to speak even more animatedly and enthusiastically about the OKRs. He finished up by telling me how proud he was of “his” team. Clearly, he meant to pay homage to them, but instead, he sounded belittling and patronizing.

My skin started to crawl, so I could only imagine how the people working for him felt.

When collecting information for a decision, we are often tempted to ask people for their recommendations — “What do you think we should do?”— but as one executive I worked with at Apple explained to me, people tend to put their egos into recommendations in a way that can lead to politics and thus worse decisions. So she recommended seeking “facts, not recommendations.”

“Any questions?” Mark concluded.

All hands and eyes were cast firmly downward, so I asked the room. “If Mark hadn’t decided on these OKRs, what would you all have planned to do next quarter?”

There was a collective exhale. Reluctantly, the young woman who’d clutched her head at lunch spoke up. While Mark’s vision was inspiring, she worried that it just wasn’t realistic. She calculated how much time it would take to do what he was suggesting, and it became clear that everyone would be working 85 hours a week.

Others chimed in. He had badly underestimated the lag time in a system that made work less efficient than it should be. They’d been trying to fix it, but the problem was proving intractable.

A conversation started. It seemed that, while Mark’s proposed goals made sense in theory, his team knew that there were major obstacles that made his plan impracticable.

He had dismissed those obstacles as mere “implementation details,” but, after listening to his team, it was clear that he’d skipped the important steps of “listen,” “clarify, “debate,” and “decide” and instead gone straight to “persuade” mode.

It was pretty clear to me that:

- His decisions were not grounded in the facts;

- Even if his decisions were the right ones, nobody was going to execute on them;

- He was in danger of losing his team if he hadn’t already.

I proposed that we finish going around the table, just to hear everyone out. Then we could regroup the following day.

This is a common mistake that is not limited to new managers. George W. Bush famously said, “I am the decider.” Part of the reason it was so funny was that he wasn’t in fact the decider, and he seemed to be the only one who didn’t know it.

If being elected as president of the United States doesn’t grant you automatic decision-making power, becoming a manager or even CEO of your start-up definitely doesn’t grant you “decider” status.

In his book A Primer on Decision Making, James March explains why it’s a bad thing when the most “senior” people in a hierarchy are always the deciders.

What he calls “garbage can decision-making” occurs when the people who happen to be around the table are the deciders rather than the people with the best information. Unfortunately, most cultures tend to favor either the most senior people or the people with the kinds of personalities that insist on sitting around the table.

The bad decisions that result are among the biggest drivers of organizational mediocrity and employee dissatisfaction.

That is why kick-ass bosses often do not decide themselves, but rather create a clear decision-making process that empowers people closest to the facts to make as many decisions as possible. Not only does that result in better decisions, but it also results in better morale.

2. The decider should get facts, not recommendations before making decisions

When collecting information for a decision, we are often tempted to ask people for their recommendations — “What do you think we should do?”— but as one executive I worked with at Apple explained to me, people tend to put their egos into recommendations in a way that can lead to politics and thus worse decisions. So she recommended seeking “facts, not recommendations.”

Of course “facts” come inflected with each person’s particular perspective or point of view, but they are less likely to become a line in the sand than a recommendation is.

3. Go spelunking before making decisions

As the boss, you do have the right to delve into any details that seem interesting or important to you. You don’t have to stay “high level” all the time. Sometimes you will be the decider. And even when you’ve delegated the key decisions, you can still plunge into the details of some other, smaller decision from time to time.

You can’t do that for every decision, but you can do it for some of them. I call this “spelunking” in your organization, and it is a good way to find out what’s really going on. It’s also a good way to put bosses and their direct reports on more equal footing — to show that nothing is “above” or “below” anyone’s concern.

Also, when you are the decider, it’s really important to go to the source of the facts. This is especially true when you’re a “manager of managers.”

You don’t want the “facts” to come to you through layers of management. If you ever played the game “telephone” as a kid, you know what happens to “facts” when they get passed around too many times.

In order to make sure they were able to understand and challenge facts as presented, leaders at Apple were expected to know details many “layers” deep in their organizations. If Steve Jobs was making an important decision and wanted to understand some aspect of it more deeply, he’d go right to the person working on it.

There were numerous stories about relatively new, young engineers who’d return from lunch to find Steve waiting in their cube, eager to ask them about a specific detail of their work.

He didn’t get this information filtered to him through the person’s boss or through the person’s boss’s recommendation; he went straight to the source.

The more often you can do that, the more empowered your whole organization feels.

4. Hold ‘Big Decision’ Meetings

Big decision meetings typically but not always follow a big debate meeting. They serve two important roles. The first is obvious: to make important decisions.

The second, though, is subtler. It can be hard to figure out when to stop debating and start deciding. I have never discovered any absolute principles to answer that question.

The simple act of being explicit and conscious about when I’m deciding versus when I’m debating is the single most helpful way to figure out when a decision really needs to be made. That’s the main reason why I recommend two separate meetings.

The logistics and norms of these meetings are the same as those of the “big debate” meetings. The leader of the meeting is the “decider,” whom you will have appointed in your staff meeting.

The only people required to attend are those identified in your staff meeting, but anyone can attend. Notes should be taken and made available to all relevant parties. Check egos at the door. No winners or losers.

The product of “big decision” meetings is a careful summary of the meeting distributed to all relevant parties.

It’s important that the decisions are final, otherwise, they’ll always be appealed and will really be debates, not decisions. You’ll need to abide by the decisions made in these meetings just like everyone else.

If you know it’s a topic you have strong opinions on, feel free to either attend the meeting or to let the decider know you have veto power.

If you have veto power, the decider should send the decision to you to approve or disapprove before the notes go out more broadly. Use this power sparingly, though, or the meetings will become meaningless.

***

This post has been excerpted from Radical Candor: Be a Kickass Boss Without Losing Your Humanity (get bulk book discounts for teams!). Learn more about the GSD Wheel in chapters 4 and 8 of Radical Candor and download our reading guide to test your knowledge of the concepts as you go. Check back soon for the next steps in the GSD wheel, Persuade and Execute. (Read the previous post about debating ideas >>)

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Sign up for our Radical Candor email newsletter >>

Shop the Radial Candor store >>

Need help practicing Radical Candor? Then you need The Feedback Loop (think Groundhog Day meets The Office), a 5-episode workplace comedy series starring David Alan Grier that brings to life Radical Candor’s simple framework for navigating candid conversations.

You’ll get an hour of hilarious content about a team whose feedback fails are costing them business; improv-inspired exercises to teach everyone the skills they need to work better together, and after-episode action plans you can put into practice immediately to up your helpful feedback EQ.

We’re offering Radical Candor readers 10% off the self-paced e-course. Follow this link and enter the promo code FEEDBACK at checkout.