Gender & Radical Candor: Why Gender Politics & Fear of Tears Makes Radical Candor Harder for Men

I had such an interesting talk with the folks at First Round Capital about gender bias and Radical Candor. Read the full article, or check out these...

When I was a child, my family used to have dinner every Sunday night with my grandparents. My grandfather said grace: “Lord, make us grateful for these and all our blessings, and keep us ever mindful of the needs of others.” When I turned twelve, I was sometimes asked to say grace, and I invariably got the second part wrong: “keep us ever needful of the minds of others.”

Recently, I came to see the wisdom of those mixed-up words. Bob Vallone, a great engineer who advised me on building an app, studied with two great psychiatrists, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky.

Recently, I came to see the wisdom of those mixed-up words. Bob Vallone, a great engineer who advised me on building an app, studied with two great psychiatrists, Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky.

He advised me to read Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman. This book reminded me how “needful of the minds of others” we really are as a species, and why Radical Candor is so important for productive collaboration. Somebody in the office who will go unnamed is rolling his eyes at yet another academic reference from me, so I’m also reading Michael Lewis’s new book, The Undoing Project: A Friendship That Changed Our Minds which is about Kahneman’s relationship with Tversky, one of science’s great partnerships.

Kahneman explains that there are two very different mental systems in our minds--the fast-thinking system and the slow-thinking system. The fast-thinking system knows just by glancing at somebody if they’re about to hit you--and prompts you to move out of harm’s way. The slow-thinking system multiplies 17x24. The slow-thinking system also, we imagine, makes calculated, conscious decisions about how we behave and why.

However, our slow, conscious thinking system is hijacked far more often than we imagine by the fast-thinking system. We couldn’t survive without our fast-thinking system, so we can’t reject it out of hand. But it can be problematic because the fast system is also the source of bias and errors of judgment that we’d never make if we just stopped and thought for a moment. Because it’s so much faster and more energetic, it often overrides our slow-thinking system. Since our slow-thinking system is the seat of conscious thought and decision-making, it’s uncomfortable to realize how often it’s hijacked by the faster system with all its bias and poor judgment.

According to Kahneman, when the fast system is in operation in our minds, it’s virtually impossible for the slow, conscious system to kick in without outside intervention. So when our fast system prompts us to do or say something out of line with what our slow system would do, we need other people to see our mistake and bring it to our attention.

As Kahneman says, “It is much easier, as well as more enjoyable to identify and label the mistakes of others than to recognize our own. Questioning what we believe and want is difficult at the best of times, and especially difficult when we most need to do it, but we can benefit from the informed opinions of others.”

In other words, we ARE ever needful of the minds of others. We need other people to challenge our fast thinking, so that we can pause and give our slow thinking system a chance to catch up. It’s almost impossible to be self-aware enough to interrupt our own biases. We need others for that. Gender or racial or political biases need interrupting. But there are also a whole host of less charged, still pernicious biases that need interrupting, too. Of course, we need people to challenge our slow thinking as well, but let's focus on fast thinking for this post.

One example Kahneman uses in his book is this: you meet Joan at a party and find her personable. Then, somebody asks you if she should be asked to donate to a charity. “Yes!” you say. “Joan is generous.” Of course, you know exactly nothing about whether Joan is or isn’t generous, or whether Joan would support the cause in question. But the fast-thinking system groups positive attributes together in the absence of information. So now, having found Joan personable, you believe Joan is generous, and that she agrees with your cause. This is called the halo effect.

Let’s say that Jack and Jill just met a new employee, Andy. Andy made a good first impression on Jill with a funny analysis of a baseball game the night before. Jack asks whether they should put Andy on a creative project that requires writing and acting skills. “Sure! He’d be great!” says Jill. Like all of us, Jill is subject to the halo bias. She meets Andy, likes him, finds him funny, and thinks he must be creative and theatrical as well. Of course, this is ridiculous, but we all make that kind of “halo effect” mistake. If Jack doesn’t challenge Jill by asking, “How do you know he’d be great?” she’s not likely to be aware of the halo bias. And Andy, who may very well be very analytical and suffer from terrible stage fright, could get put on the wrong project.

Of course, the bias can go the other way as well. If the first time you met Joan she had just taken a flight that messed with her ears so she couldn’t really hear what you said or connect personally with you, you might decide she is not personable. When somebody asks if you think she should be asked to donate to the charity, you might say, “No, don’t bother.” For all you know, she’s a multimillionaire with a passion for your cause. And you have no idea that an ear issue meant she couldn’t hear a word you said. All it would take to avoid this is a friend or a colleague who challenged you a little, who asked, “Why not?” And if you gave a lame answer, and that colleague said, “That’s not convincing, let’s learn more,” you’d be glad.

Another good example of how the biases of our fast-thinking system leads us astray is what Kahneman calls “Answering an easier question.” He says, “If a satisfactory answer to a hard question is not found quickly, our fast thinking system will find a related question that is easier and will answer it.”

For example, Kahneman found that when people were asked “This woman is running in the primaries. How far will she go in politics?” they tended instead to answer the easier question, “Does this person look like a political winner?” They substituted one easier to answer question for another.

It’s easy to see how this kind of bias plays out in interviews. Answering the question, “Would Tom be a good engineer on this project?” is hard. So the fast-thinking system will try to answer an easier question instead: “Do I like Tom?” Now, if you hate Tom’s guts you probably shouldn’t hire him. But just because you like Tom doesn’t mean you should hire him...

This bias can also play out in questions like, “Should we enter the Lithuanian market or the Macedonian market first?” All too often the fast-thinking brain serves up, say, a memory of a great vacation in Macedonia and that sways your thinking, even though it should be irrelevant. If a colleague has been hearing about that great vacation for years and can joke, “You are just in favor of Macedonia because of that vacation you took there back in 1984!” it can not only create a light moment in the meeting, it can snap your slow-thinking system into high gear.

A simple question that Kahneman proposes we ask each other to challenge biased system one thinking is, “Do we still remember the question we are trying to answer? Or have we substituted an easier one?”

I’ll share a real example of bias that my former colleague Russ Laraway interrupted for me by challenging my thinking. When I was sixteen I got invited to hear a general give a lecture. I’m not sure what he really said, but my self-righteous 16-year-old memories consist of a bunch of numberless graphs explaining that we needed to build more nuclear weapons because the Soviets could destroy the world four times over, so we needed to be able to do it five times over. Ridiculous, right? Thus a peacenik was born. Over the course of the next couple of decades, an anti-military bias solidified in my thinking without my awareness. And it expanded. And expanded.

Fast-forward a couple of decades and I’m in a little, over-heated room at Wharton interviewing Russ for a job at Google. I had a bad cold and had taken too much Benadryl the night before. I was in no mood to have my prejudices challenged. When I glanced at Russ’s resume just before he walked in the room and saw he was an ex-Marine, I wondered why I was even talking to him. All I wanted to do was to curl up in a ball in the corner of the room and go to sleep. Instead, I was talking to this guy who was clearly not a fit for Google. Google=entrepreneurial. Marines=command and control. Right?

I listened to Russ politely for about 30 seconds, and then, hoping to cut the interview short for a cat nap, I suggested that he was not a good cultural fit. I was pretty Obnoxiously Aggressive. (Blame it on Benadryl!) But Russ took no offense. He described my biased view of the military perfectly. “That’s probably what you imagine, right?” I had to admit it was so. Then he described in vivid detail what it was really like--the chaos of combat, and how he had to deal with ambiguity, take initiative, and rapidly and flexibly assess context and take action to change it. In about four minutes, he convinced me that I didn’t even know the half of what it meant to be entrepreneurial and that I had a lot to learn from him.

When we are making a mistake we’d rather not make, almost nobody is self-aware enough in the moment to see it. If we are open to the people around us giving us a heads up, and if they are willing to hold up a mirror, life gets much better. This is why giving, getting, and encouraging feedback at work helps us do the best work of our lives, become our best selves, and form the best relationships of our careers.

How to use the Radical Candor Order of Operations >>

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

I had such an interesting talk with the folks at First Round Capital about gender bias and Radical Candor. Read the full article, or check out these...

One of the things that I had to confront when I wrote the follow-up to Radical Candor, Radical Respect, is that bias, prejudice and bullying often...

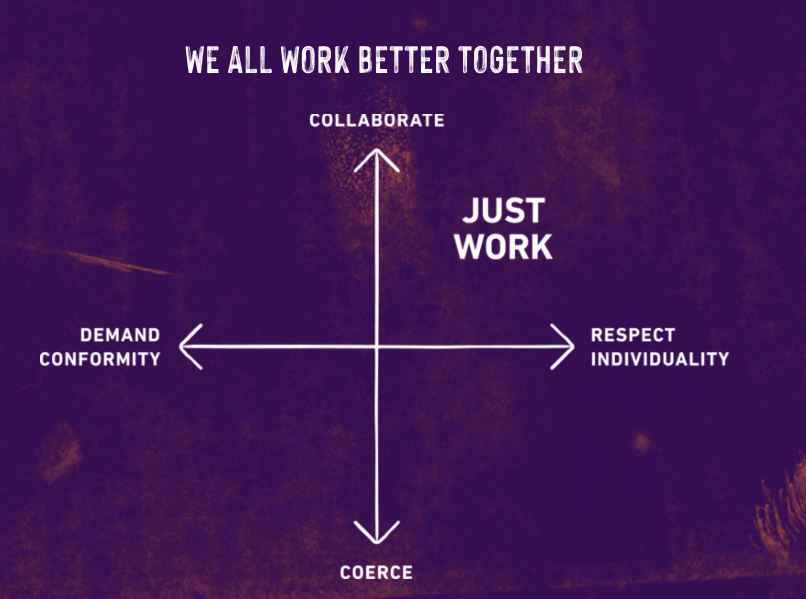

By Kim Scott & Trier Bryant We―all of us―consistently exclude, underestimate, and underutilize huge numbers of people in the workforce even as...