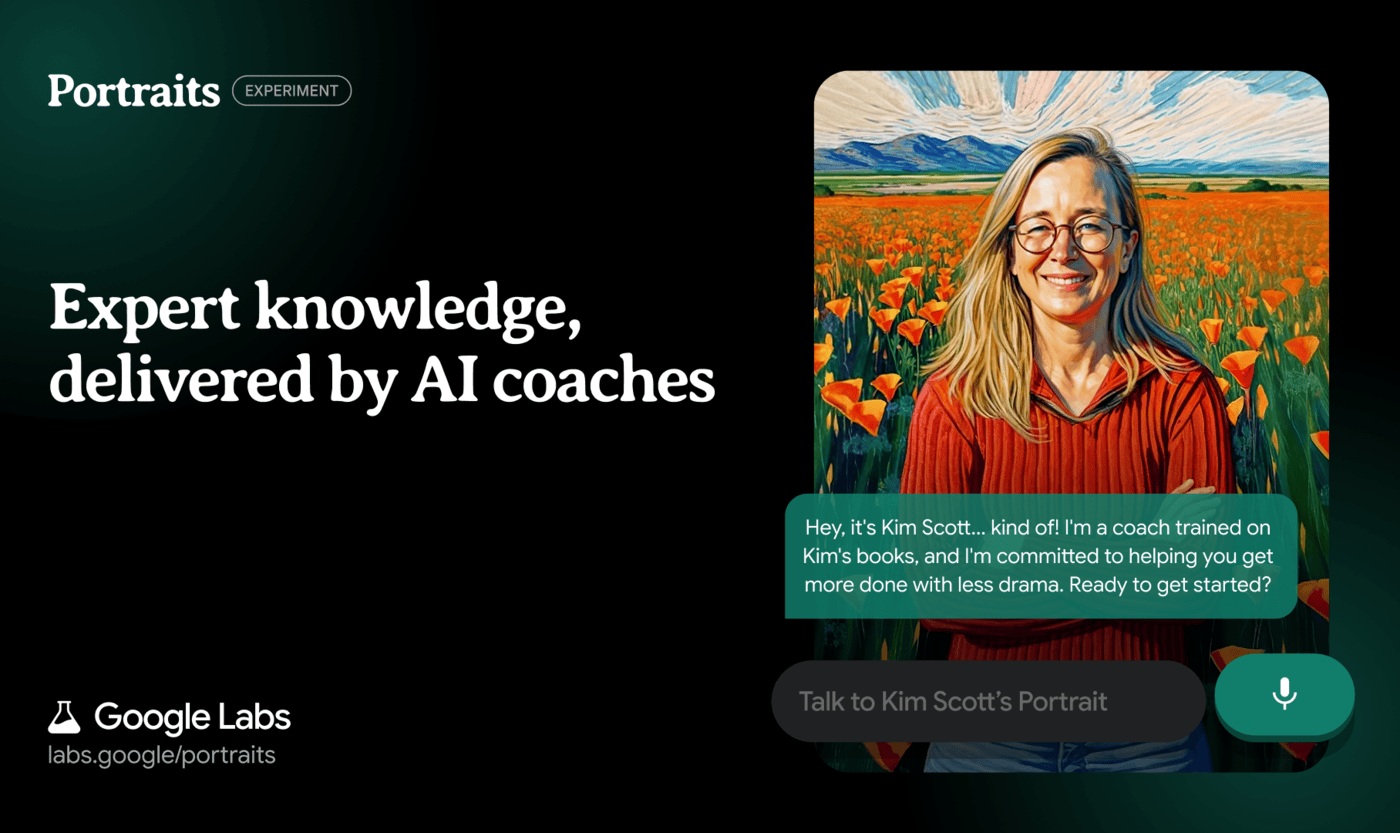

Now You Can Talk Radical Candor 24/7 With the Kim Scott Portrait

Kim Scott is the author of Radical Candor: Be a Kick-Ass Boss Without Losing Your Humanity and Radical Respect: How to Work Together Better and...

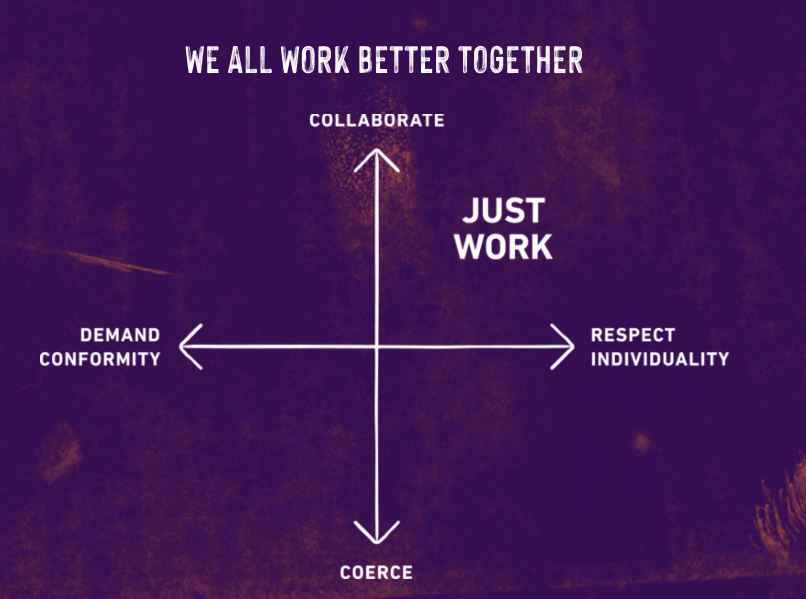

We―all of us―consistently exclude, underestimate, and underutilize huge numbers of people in the workforce even as we include, overestimate, and promote others, often beyond their level of competence. Not only is this immoral and unjust, but it’s also bad for business. Just Work is the solution.

JUST WORK is Kim Scott’s new book, revealing a practical framework for both respecting everyone’s individuality and collaborating effectively. This is the essential guide leaders and their employees need to create more just workplaces and establish new norms of collaboration and respect. We talked to Kim about what inspired her to write JUST WORK.

Tell us about your decision to follow up on the insights you offered in Radical Candor with this book. What, in your own life or in broader society, helped demonstrate to you that there was a need to focus on these specific themes at this particular cultural moment?

My first book, Radical Candor, did a great job painting a picture of how things ought to be at work: we get more done and we like each other better when we Care Personally and Challenge Directly. But I couldn’t create BS-free zones at work if I was in denial about the nature of the BS.

And here was the thing I didn’t want to admit, even to myself. Radical Candor works. But because the book does not directly address underlying systemic issues of sexism and racism, nor does it fully speak to cultural and identity differences, putting into practice some of the specific advice in Radical Candor can be more difficult for some people.

Many women told me that Radical Candor felt risky. When a woman is radically candid, she often gets called bitchy, abrasive, bossy, and so on. Furthermore, the competence/likability bias is real.

Radical Candor helps you be more competent at your job. But for women, there is a rub: the more competent a woman is, the less people, including her boss, like her. And when the boss doesn’t like you, it’s hard to get promoted. Is this a reason to be less competent? No, of course not. But it puts women in an unfair catch-22. This kind of bias impacted the ability of different people to employ Radical Candor in different ways.

James, a participant in a seminar I led, pointed out how differently people respond to him than to me when each of us walks into a room. He was correct. I am a short white woman. He is a tall Black man. We share a problem: people often have incorrect preconceptions about who we are based on our height, gender, and race; as a result, people are apt to misinterpret or underestimate us. Both of us have experienced bias, prejudice, bullying, harassment, discrimination, and physical violence — but in very different ways.

It would have been ignorant of me to say that the way I dealt with my version of the problem was the way he should deal with his version. Black women told me that they felt Radical Candor was a riskier strategy for them than for white women. When I did a training at a company led by Michelle, a CEO who is Black, she told me she had to be exceedingly careful when she offered Radical Candor.

Only at that moment did I realize that I’d known her for the better part of a decade and had never once seen her appear stressed or angry. What did that repression cost her? Why had I never noticed this extra tax she had to pay? Radical Candor works, but it is easier for straight white men to put it into practice than for anyone else. That is a problem.

JUST WORK is equally for everyone. And while many of my stories will center on gender and race, I hope the solutions will extend to workplace injustice in all its manifestations. Once we learn how to interrupt one kind of bias, it’s easier to change the often unconscious thought patterns that can lead to other kinds of bias, or worse. When we clean up these misconceptions and the behaviors that go with them, we build happier, more productive workplaces.

Trier Bryant, CEO and co-founder of Just Work the company, and Kim Scott, author of Just Work the book and co-founder of the company.

Sign up for Just Work events >>

Trier Bryant, CEO and co-founder of Just Work the company, and Kim Scott, author of Just Work the book and co-founder of the company.

Sign up for Just Work events >>

One particularly important point in JUST WORK is that creating fairer, better workplaces is not only moral but also good for business. You write, for example: “JUST WORK is about fairness. It’s also about enlightened self-interest.” Can you expand on your definition of “enlightened self-interest”?

The essence of effective management is hiring the right people for the right roles, helping them function well as a team so that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, and focusing on achieving results. If bias and prejudice are preventing you from hiring the right people for the right roles, you’re going to wind up with a sub-par team.

If bias, prejudice, and bullying prevent that team from collaborating effectively, then you’re going to get suboptimal results even if you manage to hire fantastic people. If struggling with workplace injustice means that some of the people you hire are unable to do their best work, you’re not going to get the most out of the individuals and out of the team collectively.

Early in my career I was underpaid and sexually assaulted at work. Did I do my best work at that job? Of course not! Who could do their best work under such circumstances? In my next job, I was paid fairly and felt physically safe at work. I was able to start a business that achieved a run-rate of over $100 million in under a year. If my first boss had paid me fairly and created a trusted reporting system for sexual assault, it might have been one of the best investments he ever made.

Expanding on that idea, are there ever situations in which the right thing to do isn’t profitable or in the interest of the company’s bottom line? If those situations do exist, how might we navigate them?

Yes, doing the right thing is of course more important than making money. And I believe that what is right and what is effective over the long term are usually well aligned. The conflict usually comes between what is moral and what is expedient for short-term profits. But in the long run, injustice doesn’t pay.

The cover-up perpetuates the crime. It may be painful to confront that an executive at a firm harassed an employee. But paying that employee off and forcing them to sign an NDA simply teaches that executive and other executives that they can get away with harassment. This kind of behavior will continue and escalate until it does real damage not only to the victims of harassment but also to the company.

In today’s workforce, what mistakes that prevent employees from just working do you see bosses make most often?

I have experienced bias virtually every day of my career. I have experienced bullying probably once a month. I have experienced real prejudice probably once a year. I have experienced physical violations only a handful of times over a 30-year career. Although being frotted in the elevator by my boss’s boss was certainly more traumatic than any microaggression I’ve experienced, I’d say the cumulative impact of bias has been more damaging to me personally than the physical violations.

However, other people have different experiences. If I were not white, I am sure I would experience real prejudice far more frequently. While the physical violations I experienced were bad, others have had experiences that are so traumatic that they’d dwarf the repetitive stress injury of bias that I experienced in my career.

So, while I can answer this question for myself, I cannot answer it for everyone or “in general.”

As you reflect on your own experiences in JUST WORK, you share some sensitive aspects of your personal history, including a long-term relationship that was ultimately unbalanced in its power dynamics and harmful to your success and happiness. How did you decide which personal anecdotes to include here and how much information about yourself to divulge?

When I started writing JUST WORK, I was so deep in denial that I didn’t think I had enough stories, and I thought I’d have to do research. Then I started writing and I realized that I had too many stories, that my experiences with workplace injustice were far too numerous to describe all or even half of them. This was a big part of my journey in writing the book — coming to grips with the things that had happened to me and how they had impacted me.

For example, when I started writing about that long-term relationship, I wasn’t at all sure it was relevant. I thought I would probably cut the story. But I never really know where I am going to go when I am writing. Part of what I love about writing is the opportunity it affords to rummage around in my own mind and see what turns up.

Sometimes I write things that really surprise me. For me, the most surprising sentence in this book was: “That was the first bit of abuse in the relationship.” When I wrote this sentence, I had to stop writing for the day and go curl up on the couch and take a nap. Until I wrote that sentence, I had not admitted to myself that I’d been in an abusive relationship. I didn’t think of myself as a person who’d spent the better part of a decade in an abusive relationship. But it was really liberating for me to come to grips with what had happened to me.

That didn’t mean I had to publish it though. I wasn’t sure how comfortable I was describing some of the more humiliating things that happened publicly. But then a former colleague read the passage and she said, “I hope you know how many people this is going to help.” And I realized that if I could help others come to grips with their abusive relationships my suffering would have meaning. So I left that part in the book, knowing that some will judge me harshly.

What steps can lower-level employees take to implement the JUST WORK model in their workplaces?

I admire the young people who are entering the workforce as I publish this book. This is a generation that is more apt to call BS on workplace injustice than any other in human history. At the same time, I love the advice that Michele Dauber, a professor at Stanford Law School, gives to her students who feel that they cannot pursue their personal dreams until they have righted all of society’s wrongs. She tells them to go out and try to get what they want, to live the life they imagined, and to insist that the older generation clean up some of the mess we’ve made.

It is the job of the younger generation to challenge the older generation, to hold us accountable for the mistakes we’ve made. And it is the job of the older generation to listen and to learn.

Specifically, what does this mean? My recommendation to people who may not feel they have a lot of power in an organization is to learn to recognize the difference between bias, prejudice, and bullying and to respond differently to each. Bias is “not meaning it,” prejudice is “meaning it,” and bullying is “being mean.”

Confront bias with an “I” statement, an invitation to the person to see things the way you do. For example, “I don’t think you meant that the way it sounded.”

Confront prejudice with an “it” statement that clearly shows the person where the line between their right to believe whatever they want and your right not to allow them to impose their beliefs on you is. An “it” statement can appeal to the law: “it is illegal to,” or to an HR policy, “it is a violation to” or to common human decency, “it is cruel to…” Confront bullying with a “you” statement.

Confront bullying with a “you” statement that shows a person there will be negative consequences for their behavior. The consequence doesn’t have to be super intense — sometimes just asking a person a question that it’s hard for them to answer is enough. For example, “What’s going on for you here?” Or “You can’t talk to me that way.”

The “I” statement invites the other person in, the “it” statement shows them where the fence is, and the “you” statement pushes them away.

This is all well and good, but what do you do when the person has power over you? When the person who is biased, prejudiced, or bullying you is for example your boss? In these cases, I encourage people to look for leverage in the kinds of checks and balances that a healthy workplace or a healthy society offer. It may feel like the person has unlimited control over you, but often we have more agency and more degrees of freedom than we at first realize.

When you document what is happening to you, you can begin to dispel gaslighting and reassert your sense of agency. When you build solidarity with others your agency is further reinforced, and you may get excellent practical advice and help as well as moral support. When you think about what other jobs you might be able to get you better understand your negotiating position.

When you talk directly with the person who is causing you harm you’ll often be pleasantly surprised. While there are risks associated with going to HR, there can also be a significant upside. Understand the trade-offs. While taking legal action may feel daunting to many, it’s useful to understand your options. And when you tell your story you can build more solidarity and also help others who may be struggling with something similar to what you are going through.

You devoted a section of this book to the topic of optimism. Can you talk about the decision to include that chapter, and expand on how you feel when you think about the future of our current, flawed workplace? What would you say to those who remain deeply dispirited about the sexism and racism that can feel baked into our culture?

As Tarana Burke said of the #MeToo movement, “It was a consciousness-stirring moment, but it’s not enough to create awareness. What matters is what we do next.” She is right.

The stories that we have read about in #MeToo and Black Lives Matter have elicited enormous empathy. But empathy for big problems can lead to burnout unless we figure out what we can do to begin solving these problems. As Ibram X. Kendi wrote, denial is the heartbeat of racism. And when we feel helpless in the face of a problem, we tend to retreat into denial. That is why it’s so important to me to begin to identify solutions, things we can do to begin improving the situation today. Even if the things we do don’t solve the whole problem overnight, if we are moving in the right direction, we can remain hopeful.

This was a hard book to write, and there were moments of real despair in the process. So I share the pain of people who feel deeply dispirited about the sexism and racism that get baked into our culture — both our social culture and our work culture. I also felt moments of real transcendent joy as I wrote. Often the hopelessness I felt was a result not so much of the problems themselves, but of my reluctance to acknowledge them. When I let go of that fear and really examined issues I’d thought of as “too hot to handle,” I found they weren’t in fact too hot to handle. It was a huge relief.

Also, throughout my career, I have experienced glimmers of hope, and I believe that when we focus on what we can do to improve things even a little bit, without ignoring the magnitude of the problem, we chip away.

“Everything gets better when we bring home joy instead of angst,” you write. Our satisfaction and experiences at work, of course, heavily inform our overall happiness, and even for the eager and committed, improving an office’s culture can be a long, arduous process. In the meantime, how can we maintain a healthy emotional distance from our work when we leave the office without losing our passion?

I once worked for a boss who was such a belittling bully that I actually shrank half an inch while working with him. I wasn’t bringing a lot of joy home from work in those days. I want to offer compassion to people who are in such a situation. I don’t want to be a “cruel optimist” who denies suffering. At the same time, I want to offer a glimmer of hope, a way out.

How can you find joy when you are in a situation that offers very little of it? When I have been in my darkest moments, a couple of books have offered great wisdom: Alice Walker’s The Color Purple and Victor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning. Since I have never experienced anything like the kind of suffering described in these books, I wonder if I have the right to invoke them. But they have been a great comfort to me, so I offer them to you.

Alice Walker describes how we can choose to look for joy and beauty and to hold onto them, no matter how terrible things are. We can do this not in a way that denies what is happening but helps us transcend it. Victor Frankl reminds us that although we cannot choose the things that happen to us, we can always choose our response. Therein lies freedom.

Kim Scott is the author of Just Work: Get Sh*t Done Fast and Fair as well as Radical Candor: Be a Kick-Ass Boss Without Losing Your Humanity. Trier-Lynn Bryant and Kim co-founded the company Just Work LLC to help organizations and individuals create more equitable workplaces.

Kim Scott is also the co-creator of an executive education company and workplace comedy series based on her best-selling book, Radical Candor. Jason Rosoff and Kim co-founded the company Radical Candor, LLC to help people cultivate caring and candid relationships at work by implementing a feedback-first culture.

Kim was a CEO coach at Dropbox, Qualtrics, Twitter, and other tech companies. She was a member of the faculty at Apple University and before that led AdSense, YouTube, and DoubleClick teams at Google. Earlier in her career, Kim managed a pediatric clinic in Kosovo and started a diamond-cutting factory in Moscow. She lives with her family in Silicon Valley.

Trier Bryant is Co-Founder and CEO of Just Work LLC. She is a strategic executive leader with distinctive Tech, Wall Street, and military experience spanning over 15 years. She’s previously held leadership roles at Astra, Twitter, Goldman Sachs, and proudly served as a combat veteran in the United States Air Force as a Captain leading engineering teams while spearheading diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives for the Air Force Academy, Air Force, and DoD.

Trier advises leading companies like Equinox, Airbnb, SoundCloud, Alto, Rockefeller Foundation, and others on their talent and DEI strategies. Trier has an unwavering commitment to employees within organizations to create more equitable, inclusive, and thriving workplaces producing prosperous companies. She has been featured as an influential DEI practitioner by several publications and outlets from USA Today to CNN and SXSW.

Trier earned a B.S. in Systems Engineering with a minor in Spanish and Leadership from the United States Air Force Academy (Beat Army, Sink Navy) where she played Division I volleyball. She enjoys spending time with her close-knit family who taught her to live by the family motto “…good enough isn’t.”

Kim Scott is the author of Radical Candor: Be a Kick-Ass Boss Without Losing Your Humanity and Radical Respect: How to Work Together Better and...

This piece about being bullied at work by Wesley Faulkner was originally published on the Just Work blog.

OK, folks, this may seem out of left field. But here goes: I started a book group on a new app called Fable, and I think a bunch of you might really...