3 Ways to Confront Bias, Prejudice & Bullying Masquerading as Feedback

One of the things that I had to confront when I wrote the follow-up to Radical Candor, Radical Respect, is that bias, prejudice and bullying often...

One’s awareness of a negative stereotype about a group to which one belongs can actually harm one’s performance: fear of confirming the stereotype raises that person’s level of anxiety and makes it harder to perform at one’s best.

This can occur in people at all levels of organizations, including at the top, so leaders must manage it in others and be aware of it in themselves.

In Whistling Vivaldi, Berkeley psychologist Claude Steele describes how negative stereotypes inhibit people’s ability to do work they are more than capable of doing. He described a Princeton study in which students were asked to play golf.

A group of white students were divided into two groups; the first was told the task was part of an athletic aptitude test, while the second was told nothing. The white students who were told the task measured natural ability tried just as hard as the other students.

But it took them an average of three strokes longer to get through the course. They performed worse. The hypothesis was that stereotype threat (white people have inferior athletic ability) had hurt the performance.

The experiment was then repeated with Black students, and both groups performed equally. The difference, Steele explained, was that the Black students didn’t suffer a stereotype threat when it came to athletic ability.

Steele ran a similar experiment at Stanford, only this time looking at stereotype threat related to intellectual ability. He brought together a group of Black and white undergraduates and asked them to complete a section of the Advanced GRE test.

This test was beyond what they had learned, and Steele hypothesized that the frustration at not knowing some of the answers would trigger a stereotype threat related to intellectual ability in the Black students and cause them to underperform.

Indeed, the Black students did do worse than the white students on the test. To test his hypothesis that this was a result of stereotype threat and not intellectual ability or educational achievement, Steele repeated the test with a different group of Black and white students.

This time, he lifted the stereotype threat by telling the students that the test was not a test but rather a “task” for studying general problem-solving. He emphasized that it did not measure intellectual ability. This time, the Black students performed at the same level as white test takers and significantly better than the Black test takers who believed the test was measuring their intellectual ability.

Steele and other researchers have tested the impact of stereotypes on a wide variety of different biases. In another experiment, researchers gave girls five to seven years old an age-appropriate math test.

Just before taking the test, some of the girls were asked to color a picture of a girl their age holding a doll, while others were asked to color a landscape. The theory was that reminding the girls they were girls would be enough to trigger a stereotype threat: girls aren’t good at math.

And in fact, the girls who colored a landscape did better on the math test than those who colored a girl holding a doll.

Another group of researchers asked white men with good academic track records to take a difficult math test. In the control condition, the test was taken normally. In the experimental condition, the researchers told the test takers that one of their reasons for doing the research was to understand why Asian men seemed to perform better on these tests than white men.

The theory was that the stereotype threat that white people aren’t as good at math as Asian people would harm the performance of the white men on the test. This is exactly what happened.

Part of your job as a leader is to recognize and eliminate the pernicious effects of stereotype threats for the people on your team. Regardless of the stereotype in question, good, candid performance feedback can go a long way toward eliminating the stereotype threat people may be experiencing.

The key is to explain clearly what the standards are and reassure the person you’re giving feedback to that you have confidence in their abilities.

Steele describes the role of good feedback in helping people who are underrepresented overcome their stereotype threats. Straightforward critical feedback from Tom Ostrom, Steele’s Ph.D. faculty adviser, helped Steele overcome the struggles he experienced as one of the few Black students in his program.

He also references research that demonstrates this was true for Black students at other universities around the country.

If you’re a leader, get proactive. Make sure that you are aware of and managing your own stereotype threat and that you are giving everyone on your team helpful feedback.

(Note that the feedback was about the work—not about their clothing or affect or something else that might reveal bias and trigger stereotype threat.) Similarly, Stanford sociologist Shelley Correll’s research has shown that career success requires candid criticism—and that many women don’t get that kind of candor from their bosses who are men.

There is considerable evidence—both anecdotal and research-based—that good feedback, a clear explanation of expectations, reassurances that an employee can meet those expectations, and guidance when a candidate falls short are crucial in helping people who are underrepresented succeed in the workplace.

Important note: Feedback about how other people perceive a person because of bias is NOT helpful feedback. The feedback should be based on performance or behaviors that can be changed, not personal attributes.

Yet, the very people who would most benefit from good feedback get it least. Overrepresented managers are most comfortable giving feedback to employees who are “like” them.

White managers are often more reluctant to give straightforward feedback to Black employees than they are to white employees; men are more reluctant to give this kind of feedback to employees who are women, and so on.

Why? Sometimes this happens because the manager is a bully or actively prejudiced. But more often it happens because another stereotype threat is at play: fear of being seen as biased, sexist, or racist.

A desire not to be seen as biased paradoxically leads to discriminatory behavior, a failure to give candid, helpful feedback to underrepresented employees.

Therefore, the “fear of being seen as biased” stereotype threat can inhibit bosses from giving the feedback it’s their job to give.

Stereotype threat might prevent an overrepresented boss from giving critical feedback to an underrepresented person on the team. This is really unfortunate because it’s precisely that kind of feedback that will most help underrepresented people overcome their own stereotype threats and do great work.

If you’re a leader, get proactive. Make sure that you are aware of and managing your own stereotype threat and that you are giving everyone on your team helpful feedback.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

Sign up for our Radical Candor email newsletter >>

Shop the Radial Candor store >>

Book a keynote or workshop >>

Need help practicing Radical Candor? Then you need The Feedback Loop (think Groundhog Day meets The Office), a 5-episode workplace comedy series starring David Alan Grier that brings to life Radical Candor’s simple framework for navigating candid conversations.

You’ll get an hour of hilarious content about a team whose feedback fails are costing them business; improv-inspired exercises to teach everyone the skills they need to work better together, and after-episode action plans you can put into practice immediately to up your helpful feedback EQ.

We’re offering Radical Candor readers 10% off the self-paced e-course. Follow this link and enter the promo code FEEDBACK at checkout.

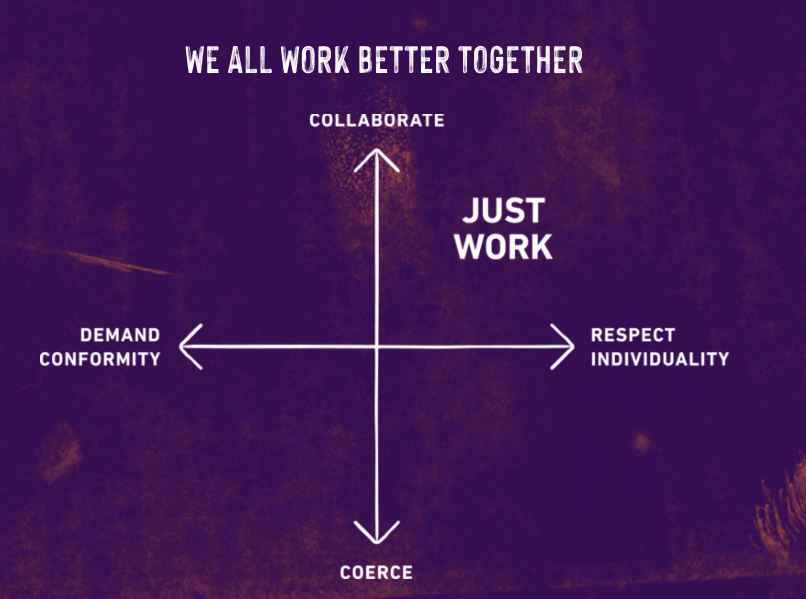

Order Kim’s new book, Just Work: How To Root Out Bias, Prejudice, and Bullying to Create a Kick-Ass Culture of Inclusivity, to learn how we can recognize, attack, and eliminate workplace injustice ― and transform our careers and organizations in the process.

We ― all of us ― consistently exclude, underestimate, and underutilize huge numbers of people in the workforce even as we include, overestimate, and promote others, often beyond their level of competence. Not only is this immoral and unjust, but it’s also bad for business. Just Work is the solution.

Just Work is Kim’s new book, revealing a practical framework for both respecting everyone’s individuality and collaborating effectively. This is the essential guide leaders and their employees need to create more just workplaces and establish new norms of collaboration and respect.

One of the things that I had to confront when I wrote the follow-up to Radical Candor, Radical Respect, is that bias, prejudice and bullying often...

Brandi Neal is the Radical Candor podcast writer and producer, and director of content creation for Radical Candor. She has 20 years experience as a...

By Kim Scott & Trier Bryant We―all of us―consistently exclude, underestimate, and underutilize huge numbers of people in the workforce even as...