Video Tip: What is Radical Candor? Learn the Basic Principles In 6 Minutes

What is Radical Candor? People often get confused about what Radical Candor really means.

6 min read

Kim Scott Aug 11, 2022 2:12:44 PM

Telling a person at the last minute that you can’t fulfill a commitment does real damage to your relationship. Of course, sh*t happens. Sometimes you can’t keep your commitments for reasons you could never have predicted. When that happens, as it inevitably will, there are real benefits to delivering bad news early.

The longer you wait, the fewer degrees of freedom the other person has to adjust, and the more damage you do to the relationship

In a good working relationship, two things happen when you deliver bad news early. As soon as you realize you will be late or need to postpone, you tell the other person. And the other person has enough experience with you keeping your commitment that it’s easy to cut you some slack this time.

I find visuals helpful, so here’s a visual reminder of why “bad news early” is so important. I am “stealing” this from Fred Kofman, who taught it to me when he was my coach at Google.

(Need help with Radical Candor? Let's talk!)

If X is the time by which you have committed to do something the sooner one tells the other person it’s not going to happen, the better.

The closer to a deadline you tell the person you’re going to miss it, the more damage you do. If you say after the date, “oh by the way that thing I promised you is still not done,” then you really do a lot of damage.

For example, let’s say I promised to write a draft of my book by August 10. I know by mid-June I'm not going to get it done.

If I tell my editor that as soon as I myself know it (mid-June) they may be frustrated but I actually build their ability to rely on me — they know that I'll tell them as soon as I know.

The sooner I tell them, the more easily they can re-order their priorities. The longer I wait, the worse it is for them — and if I wait till August 10 they’re just stuck — they can't launch some other book.

And if I wait till August 15 — five days after the deadline — to tell them I'm not getting it in, it's not only worse for them at a practical level, it's like I don't respect them enough to let them know — like I thought the deadline just didn't matter.

While most people know delaying bad news isn’t good for anyone, fear keeps many individual contributors from speaking up at work.

A study published in the Strategic Management Journal found that employees tend to distort or sugarcoat bad news because they’re afraid of being viewed negatively.

This not only damages relationships but can have a cascading effect throughout the organization.

So even if you know it’s important to give bad news early — like you’re not going to make that looming project deadline — you might delay delivering it because you’re afraid.

This is not only going to make things worse in the long run (your fear is not going to get the project done on time), it’s going to cause you a lot of psychological stress along the way.

“No one wants to hear that the work they are expecting at that very moment is far from done.”

“Here is the thing. You don’t just suddenly miss a deadline (unless you have an emergency or you scheduled the wrong day on your calendar),” Martin Luenendonk writes for the career coaching organization Cleverism.

“There are tell-tale signs that you won’t be able to meet your deadline.”

If you have bad news to deliver, just do it. Don’t succumb to magical thinking, fear, or procrastination.

Your team members are perceptive enough to pick up on non-verbal cues, even in a remote work environment. This means that what you’re not saying speaks 10 times louder than what you are.

If you’ve got bad news to deliver, don’t wait for the ever elusive “more information” if it causes you to delay action that helps the people on your team.

A study published by the IEEE International Professional Communication Conference (ProComm) found that a majority of people valued clarity, candor and directness over other characteristics when receiving bad news.

One of the study’s authors, BYU Linguistics Professor Alan Manning, explained in a news release that previous research on giving bad news has focused on making it easier for the person delivering the bad news versus making it easiest for the person receiving it.

This model leads to buffers that drag out uncertainty for the person getting the bad news.

"If you're on the giving end, yeah, absolutely, it's probably more comfortable psychologically to pad it out — which explains why traditional advice is the way it is," he said. "But this survey is framed in terms of you imagining you're getting bad news and which version you find least objectionable. People on the receiving end would much rather get it this way."

Lack of information often leads people to assume the worst. So, when you have information that affects your team members, commit to delivering it as soon as possible in a way that’s kind and clear.

No one wants to wait until after the holiday break to find out whether or not they’re getting that raise or promotion or they’re getting laid off. If you know something, say something. If you don’t, simply saying “I don’t know” can go a long way toward building trust.

Unfortunately, people are primed to mistrust you based on all the preconceived notions against bosses. You may feel like it is safe to give you the bad news early; but that doesn’t mean your employees believe it’s safe. You have got to prove to them that you are a reasonable person. Their past five bosses may have been totally unreasonable.

This means it might never feel 100% safe or comfortable or risk-free for your employees to give you feedback or deliver bad news.

Because power corrupts, the little bit of power you get when you become the boss will make people look for the worst in you, even if you are diligent about not letting it bring out your worst.

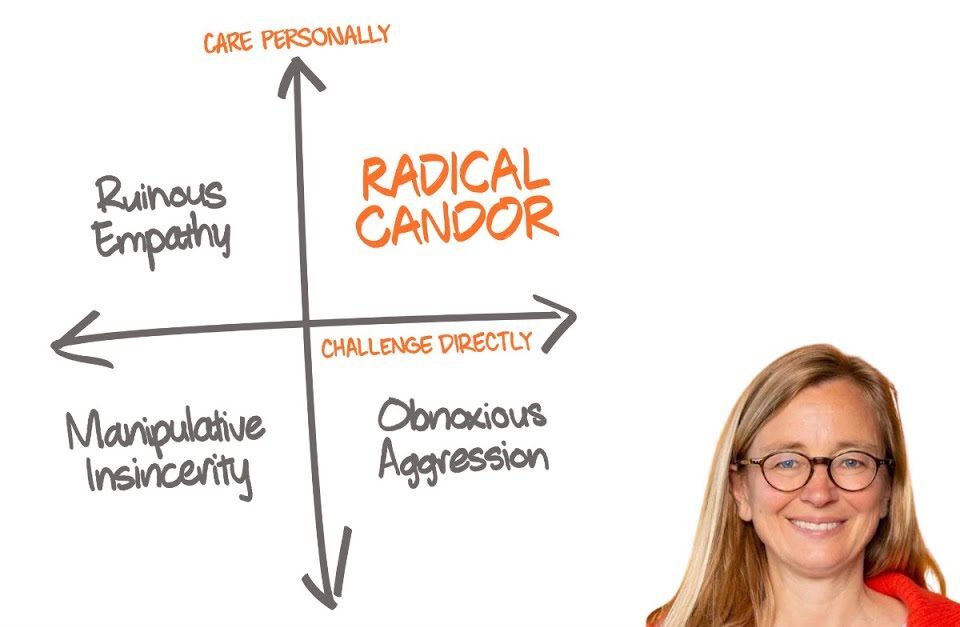

One way to get past the negative connotations of the position is to push yourself really high on the Care Personally axis.

When you show you care, you build a relationship and you build trust. People will stop seeing you as the “jerk in charge” and assuming the worst.

But you need to show that you care — it’s not enough for you to feel it. Others need to see it in action.

Harvard Business School Professor Amy Edmondson calls this psychological safety — feeling heard and acknowledged versus fearing you will be retaliated against.

It’s up to managers to create an environment in which the rewards of giving bad news or admitting a failure outweigh the risks. It’s not enough to not punish people for delivering bad news early. You have to reward them for doing it.

Praise them publicly. When people see you praising someone for telling you early they’re going to miss a deadline, it will get their attention. Of course, you may want to praise the person for hitting their previous five deadlines. You want it to be crystal clear the praise is for bad news early — not for missing the deadline.

When leaders are transparent and authentic, their teams assume good intent and are more likely to feel comfortable giving bad news early — or at all.

Brandi Neal contributed to this post.

Need help practicing Radical Candor? Then you need The Feedback Loop (think Groundhog Day meets The Office), a 5-episode workplace comedy series starring David Alan Grier that brings to life Radical Candor’s simple framework for navigating candid conversations.

You’ll get an hour of hilarious content about a team whose feedback fails are costing them business; improv-inspired exercises to teach everyone the skills they need to work better together, and after-episode action plans you can put into practice immediately to up your helpful feedback EQ.

We’re offering Radical Candor readers 10% off the self-paced e-course. Follow this link and enter the promo code FEEDBACK at checkout.

Order Kim’s new book, Just Work: How To Root Out Bias, Prejudice, and Bullying to Create a Kick-Ass Culture of Inclusivity, to learn how we can recognize, attack, and eliminate workplace injustice ― and transform our careers and organizations in the process.

We ― all of us ― consistently exclude, underestimate, and underutilize huge numbers of people in the workforce even as we include, overestimate, and promote others, often beyond their level of competence. Not only is this immoral and unjust, but it’s also bad for business. Just Work is the solution.

Just Work is Kim’s new book, revealing a practical framework for both respecting everyone’s individuality and collaborating effectively. This is the essential guide leaders and their employees need to create more just workplaces and establish new norms of collaboration and respect.

What is Radical Candor? People often get confused about what Radical Candor really means.

According to Gallup's Leadership and Management Indicator, only 21% of employees in the U.S. trust the leadership in their organization. In addition,...

Every CEO, middle manager and first-time manager I have ever worked with has struggled to figure out how to run a productive staff meeting.