This post about navigating feedback conversations on diverse teams is by Nahla Davies, a software…

6 Tips for Taking Feedback Well

Russ Laraway wrote this post about how to receive feedback. The chief people officer at Goodwater Capital who also developed Career Conversations, his book When They Win, You Win, provides a simple, coherent, and complete leadership standard that teaches managers how to lead in a way that measurably and predictably delivers more engaged employees and better business results and show organizational planners how to make their managers great!

Have you ever noticed that when it rains, everyone shows up to work talking about how everyone else can’t drive in the rain? Have you noticed that no one is showing up saying they themselves can’t drive in the rain?

I gotta believe that some of those complaining about others’ poor driving, must also be driving poorly and the target of others’ complaints.

Well, here at Radical Candor’s Global Headquarters, we get asked a lot of some version of “How do you talk to people about accepting feedback better?”

It reminds me a lot of people driving in the rain — they can see clearly when others are messing it up, but it’s sometimes a little bit harder to see it in ourselves. Just like driving in the rain, knowing how to receive feedback in the workplace is hard.

Want to learn how to receive feedback? Let's talk!

How to Receive Feedback

Personally, I’m terrible at receiving feedback in some circumstances and really good at it in others.

For example, if someone is junior to me or if I ask for feedback from anyone, I am very excited to get it. I love it. I don’t care how harsh or how scathing. The praise doesn’t go to my head and the criticism doesn’t get me down.

I can hear the feedback so clearly, am super interested in it, and it somehow feels like a problem-solving session — a discussion taking place in my prefrontal cortex, which is the problem-solving part of the brain.

Conversely, I am not good at hearing feedback when I get surprised. This morning, Kim, my co-founder, approached me while I was reviewing one of our podcast episodes to give me some feedback. For a variety of reasons, none of them good in hindsight, I felt my defenses surge.

The feedback was actually not even particularly critical, but the circumstances — the interruption, the fact that I wasn’t in that moment thinking about that particular thing, and the fact that I had already reached a similar conclusion — all somehow conspired to set off my internal alarm bells.

I didn’t let on that I was having a defensive reaction and used a simple technique (label and re-appraise) to move out of threat response and into critical thinking. Crisis averted, but it doesn’t change the fact that my threat response went off first and I had to work to suppress it and engage in the conversation.

So what can we learn from this? Am I just some super defensive guy, or am I pretty normal?

I’m going to guess that it’s much more normal for people to manifest a threat response to critical feedback than it is not to. Otherwise, critical feedback wouldn’t be so hard.

So, I’ll say “normal,” and we’re all in this together. I want to share a few tips for receiving feedback better so that you can be the change you want to see in the world.

1: Prepare Your Mind and Ask for It (Alternate “Buckle Up”)

OK, let’s talk about how to receive feedback. For starters, ask for feedback much more often. Funny thing… I talk to many, many companies every week, and they all communicate some version of their leaders not giving enough feedback and giving almost no critical feedback.

It’s no mystery that giving feedback is hard. Imagine how much easier it would become if everyone just started asking for it.

We wrote a blog post a while back on how to ask for feedback. I won’t rehash that article here because I want to focus more on the mindset of receiving feedback versus the tactics of asking for it.

When you ask for feedback, you get to set the terms — timing, mindset, even content. You can get your mind right and ready to hear tough stuff. So much of hearing feedback well is preparing yourself to hear it. Saying to yourself, “Buckle up, you’re about to get some criticism, and feedback is a gift so let’s go.”

If it helps, you can even use your best Stuart Smalley voice, because doggone it, people like you.

Also, I promise, that the more you ask for feedback, the better you get at taking it. My son is a competitive gymnast. Gymnastics is an extraordinary sport with many attributes, but one way to describe gymnastics is that you fail hundreds of times at something before you finally succeed, and every one of those hundreds of attempts will include a brief piece of corrective feedback.

The gymnasts are not explicitly asking for feedback, but they do expect it after every repetition. The gymnasts nod and try to incorporate on the next attempt. Like anything, they practice getting feedback and then get good at it.

When you ask, you communicate two things: 1) you want the feedback and 2) you are ready to hear it — two massive obstacles that feedback givers tend to stress over.

Most importantly, though, the act of asking allows you to be proactive/puts you on the front foot, and allows/forces you to prepare your mind, which in my opinion is the highest leverage activity available to help you hear feedback well.

Imagine if, in my example with Kim, I proactively grabbed her to talk about this topic that she hit me with. I go into that conversation saying “What do you think?” ready to hear her, ready with my own theory, ready to solve a problem rather than allowing myself to be surprised.

Of course, it’s impossible to never get surprised by feedback, and we must all work on getting ourselves into a mode when feedback is offered, but I think that starting to more frequently ask for feedback helps you get the feedback you need and helps you get it with the right mindset to be able to truly hear it and take it on board.

2: Don’t Get Mad Get Curious

In our article about how to get feedback, we talk about listening with the intent to understand and not respond… or cross-examine. How you react in the split second someone starts to give you critical feedback is a crucial moment.

Fly off the handle and you will set your relationship back months. Calmly listen and manifest as curious, and you can advance your relationship by weeks!

Yes, I do believe there is more damage inflicted by a defensive reaction than growth realized from a good one. There’s one simple phrase that if repeated (I mean this literally) in your brain over and over, you can help yourself to react well to the feedback.

Don’t Get Mad, Get Curious, a handy little phrase coined by Fred Kofman in Conscious Business. Just keep saying that in your head.

What does this mean? If you get deeply curious about the feedback you are receiving, it starts to feel more like a problem to solve. Humans like solving problems.

Bonus: this is a problem to solve where the subject is something else humans love: themselves. Sentiments that can really help:

- “Ooo. That is interesting. Tell me more about that.”

- “Ak! I didn’t realize that by saying that thing that way I was upsetting the other team. How can we tidy things up there?”

- “Oh my gosh, that is so interesting that is how I’m showing up. Of course, I don’t mean to, but am I understanding correctly that you see X, Y, and Z?”

3: Label and Reappraise

I love David Rock’s book, Your Brain at Work. He covers a lot of ground in the book, but the central theme is the SCARF model, a set of social threats (Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness, Fairness) you are likely to experience in the workplace, or even in life.

Those threats of course are far less dangerous than, say, being chased by a lion, but to your brain, they feel about the same.

One of the coping mechanisms he tees up is Label and Reappraise. As you start to feel an emotion or threat, label that threat (give it a name) and then reappraise it (assess it again in a different way).

This is a way to actively “switch” your mind out of emotion and threat and into problem-solving and critical thinking. As Rock describes, your limbic system (the system that deals with threat response and emotion) and pre-frontal cortex (the part of your brain that is involved with thinking and problem-solving) do not actually work together.

These two systems compete for resources, glucose, and oxygen. The biggest problem is that it’s been an evolutionary necessity for much longer to have an excellent threat response than to have great problem-solving skills.

So the limbic system is located in the largest, oldest, most efficient part of the brain, and it easily dominates the competition for resources. This is why it’s so hard to think when you’re scared, for example.

So when you label a threat or emotion, you put yourself in a problem-solving activity. You have to search for the right way to describe this emotion you’re having. In the case of my conversation with Kim this morning, it was simple: defensive.

“You’re being, defensive, Russ,” step 1 achieved. The reappraisal step was similarly simple, but not easy. “She’s got your back like she’s had for a decade, and this is actually a topic we both care about deeply. She’s just trying to be helpful.”

I don’t mean to make this sound magical, but this is all exactly true. Within seconds we were laughing about this topic, enthusiastically agreeing with each other on the things we’re going to change to achieve the results we want.

A simple action plan was hatched, and collaboration was achieved.

4: Don’t Rely on Being Your Own Worst Critic

“I’m my own worst critic.” You hear this a lot, don’t you? Maybe even in your own head? It’s some version of “I don’t really need much feedback because I’m my own worst critic.”

If I’m being honest, this is something that runs through my head a ton, but it’s wrong. Here are some of the common phrases that folks think and say:

- No one is tougher on me than me.

- No one has a higher standard for me than I do.

- I am extremely self-aware.

- I am likely to see my mistakes long before anyone else does

There are a bunch of problems with this mentality, even if some of those things seem true.

Let’s start with this. Rory McIlroy is, at the time of this writing, the number two golfer in the world. I chose Rory because, among the top 10 PGA Tour golfers in the world, he’s the closest thing to a household name.

Rory McIlroy has at least two coaches, a swing coach, and a putting coach. Don’t you think Rory McIlroy is hard on himself? Can’t he videotape himself and analyze his own swing?

Isn’t it likely that to have become the number two golfer in the world, he has much higher standards for himself than 99% of humans?

But he still needs a coach. Said differently, HE PAYS PEOPLE TO GIVE HIM CRITICISM despite his standing as the second-best golfer in the world.

You’re a pretty good employee, but almost certainly not the number two employee in the world. No offense, it’s just statistically unlikely. Would it ever cross your mind to pay someone to criticize you?

Great news. You don’t have to. Your company does that already. They pay your manager, your peers, and your team to criticize you.

I think the insight here is that how we show up at work is complex. Our own version of that might be very accurate because of our high standards and high self-awareness, but it’s almost certainly not entirely accurate, and more likely, a lot less accurate than we think.

You have to believe that receiving feedback from people around you can advance your thinking, add texture, add depth, and make you just a little bit better.

Use those high standards you have for yourself to say, “They are so high, I even want the tiny little things that only the people around me can add.” Here’s a way to enable this thinking:

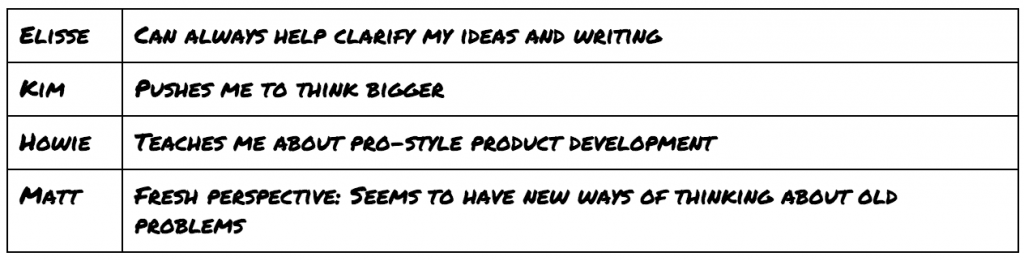

Write down in a private notebook, the names of the people you work most closely with each week. Maybe 5-10 people at most. For each person, write down three things that you theorize they might be able to help you with.

You don’t have to act on this just yet; mostly, you are embarking on a process to convince yourself that the folks around you do have something to offer.

For example, my teammate, Elisse, is a very structured and clear thinker. I have filed away in my brain that I can always count on her to help me structure and clarify my thinking and my writing. (See the photo of my list above.)

5: Stop Trying to “Get an A”

Related to the mindset: “I’m my own worst critic” is the idea that when you are receiving feedback, you are trying to get an A.

When I was in the Marines and attended The Basic School with 250 fellow 2nd Lieutenants, we had a pejorative term for the over-participators. We called them “spring-butts”. The basic insight is that when you answered a question in class, you were expected to stand up, introduce yourself, and then ask the question.

Out of the 250 lieutenants, some guys just couldn’t help themselves, spring-butts to the core, and it felt like they were “trying to get an A” even though that interaction had nothing really to do with your evaluation in school.

When you are self-aware, be mindful that while you’re receiving feedback, you are at risk of over-participating and manifesting like the person who is “trying to get an A.” Curious, engaged, writing things down — all great behavior.

On the other hand, interrupting, and even nodding in anticipation of the next sentence can make it seem like you are not really listening. You run a risk of showing up like “You’re telling me stuff I already know.”

This one is a little bit counterintuitive because I know when I’ve been in this mode, I’ve been thinking in my head, “Yep, got it. Agree. Agree. Agree. I am so damn self-aware, check me out.”

All of this is a form of affirmation bias, “I already see this thing this way, and this feedback affirms it,” when the opportunity is to listen and advance your thinking rather than affirming it.

So, instead of just agreeing with the feedback giver, interrupting them with your “yeps” and “totallys” or seemingly impatiently anticipating each new sentence, try to advance your thinking by just listening quietly.

When they sound done, as always, check for understanding. “So, what I think I hear you saying is that if I were to change A and B, you think it would help me in X & Y ways? Do I have that right?”

Simple. But not easy.

Look, I’m with you. I will often have given myself the feedback weeks before someone else would even think to. Let’s agree this self-awareness is generally a strength, but it becomes a weakness — and frankly an arrogance — when we allow our belief in our ability to self-assess to get in the way of hearing new assessments from those around us.

6: Follow up

I would argue that the definition of taking feedback well is showing that you understood the feedback and that you plan to do something about it.

Take a moment in the conversation to communicate a couple of things:

- I heard you. This is achieved not by using the actual phrase “I heard you,” but by repeating back what you think you heard. Something like, “OK, lemme recap what I think you’re saying…”

- Here’s what I will do. It need not always be the case that you will take the feedback on board. But it should ALWAYS be the case that you will take some action, even if it’s just to think about the feedback and follow up in a week with an action plan. Communicate your intentions. “Well, thanks — you’ve given me a lot to think about here, and I appreciate that. Do you mind if I take a week to digest this and come back to you with how I’m thinking about taking action?”

I want to highlight that in the conversation it’s only natural for you to be mentally assessing the quality of the feedback and the quality of the delivery.

Let’s acknowledge two things: 1) feedback and delivery quality will be highly uneven and 2) you are probably more primed to reject the feedback than to hear it. Try with all your might to hold your feet to the fire that your objective in this moment is not to assess the feedback or the quality, but simply to understand it. You can evaluate it later when you have some time to reflect.

After the conversation, of course, you must follow up. Proactively put that topic on the agenda for your next meeting with that person and discuss your insights and some things you are planning to do to improve.

Heck, it might even be that you’re planning to do nothing. In some cases, that might be the most appropriate thing, but taking the time to say “I really thought about this, and I’m not sure there’s a lot of action for me to take right now. Will you just help me keep an eye on this and I’ll check back with you in two months?” Then you darn well better follow up in 2 months.

The point is simple — most people find giving critical feedback hard. No one really loves doing it, and we’re definitely not doing it for our health. It’s important to give the feedback giver some kind of payoff or else you’re likely to stop getting feedback.

Remember: the purpose of criticism is to help people improve. To improve your work and improve your behaviors. If you improve your work and your behaviors, you will find more success. It’s in your best interest to get as much of this as possible, not to avoid it or cut it off.

Aggressively ask for feedback, treat the feedback like a problem to solve around your favorite topic (you), and proactively follow up on the feedback. Be the change you want to see in the world. You can be the one to catalyze a culture of feedback.

*This post was updated 2/8/24.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

- Take the Radical Candor quiz >>

- Sign up for our Radical Candor email newsletter >>

- Listen to the Radical Candor podcast >>

- Shop the Radical Candor store >>

- Get the “Radical” books >>

- Get Radical Candor coaching and consulting for your team >>

- Get Radical Candor coaching and consulting for your company >>

If you understand the importance of receiving feedback in the workplace, then you need The Feedback Loop (think Groundhog Day meets The Office), a 5-episode workplace comedy series starring David Alan Grier that brings to life Radical Candor’s simple framework for navigating candid conversations.

We’re offering Radical Candor readers 10% off the self-paced e-course. Follow this link and enter the promo code FEEDBACK at checkout.