This post about how to fix communications issues in the workplace is by Zachary Amos,…

Navigating Radical Candor and Cultural Differences

When talking about Radical Candor, I often get asked about how it applies to different cultures. Can Radical Candor be used for feedback and interactions across countries and cultures? Do you have to approach it differently for different cultures? Here are my thoughts on Radical Candor and cultural differences:

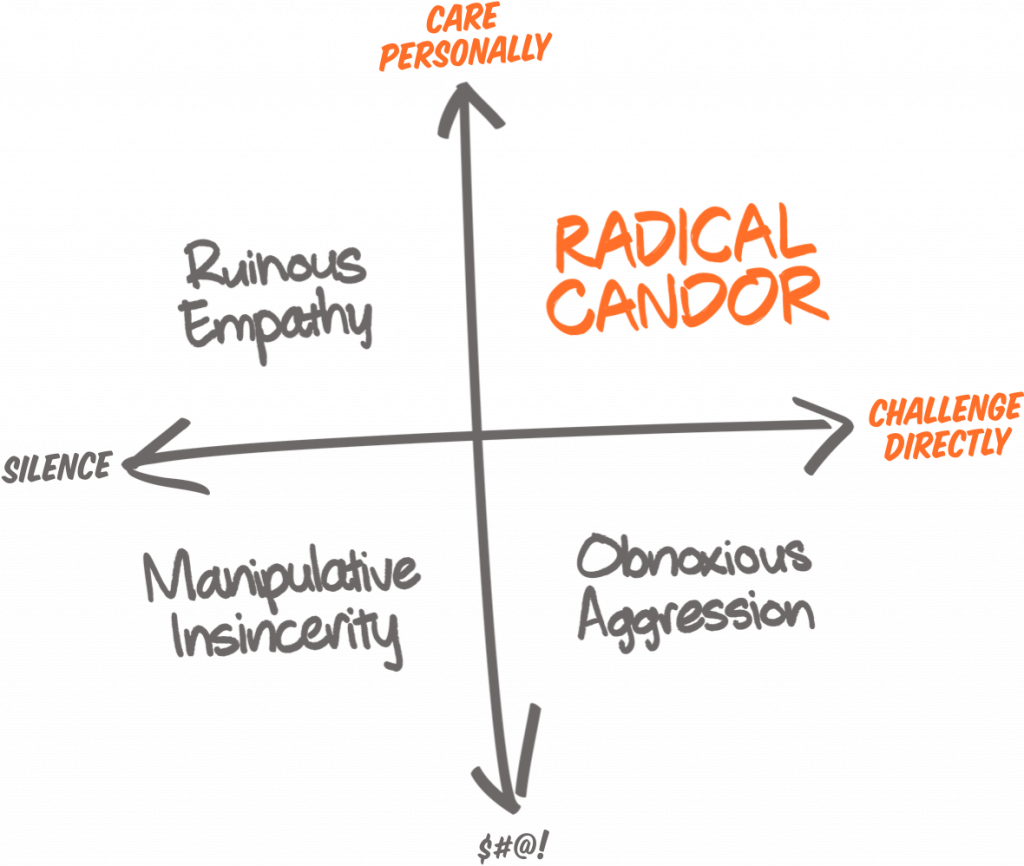

Radical Candor is universally human, but interpersonally and culturally relative

The key is that Challenging Directly and showing you Care Personally are both sensitive to context and perception; they get measured at the listener’s ear, not at the speaker’s mouth.

Radical Candor works only if the other person feels you are Challenging Directly and showing you Care Personally. What seems Radically Candid to one person or team may feel too obnoxious or too touchy-feely to another. Going from one company to another or from one country to another, may mean even more differences in perception, so you need to consider individual and cultural preferences and adjust accordingly.

Let me share some stories to show how Radical Candor and cultural differences has played out for me.

When the Culture Expects Direct Challenges

Shortly after I graduated from business school, I took a job with Deltathree, a voice over IP start-up based in Jerusalem. I was raised in the American South, where people will do almost anything to avoid conflict or argument. In Israel, the opposite was true. Conversations seemed to encourage conflict.

I’ll never forget overhearing Noam Bardin, Deltathree’s COO, yelling at an engineer, “That design could be fifteen times more efficient. You know you could have built it better. Now we’re going to have to rip what you did out and start over. We’ve lost a month, and for what? What were you thinking??”

I was a little shocked by this — I don’t think I had ever heard such a direct challenge in the workplace. But the engineer seemed to think this challenge was perfectly acceptable.

As I spent more time in Jerusalem and built relationships with the Israelis on the team, I began to understand the Israeli culture better. I began to understand that in the workplace and elsewhere, it was OK to challenge everything. It was not a sign of disrespect to argue vehemently with each other; rather it was a sign that the issue at hand was an important one to think about and discuss. I realized that Noam’s challenge to the engineer was a sign of respect.

When the Culture is Reluctant to Challenge Directly

I had a very different experience when I managed a team in Tokyo a few years later. The team there was enormously frustrated with how the Product team at Google’s U.S. headquarters was approaching ads in mobile applications. But the Japanese team felt that it would be a sign of disrespect to voice these problems to the team responsible for product management, so they weren’t getting fixed. When I pushed them to challenge the approach to mobile applications at Google headquarters, the team just stared at me as though I were crazy.

Trying to get the team in Tokyo to challenge directly the way Noam Bardin did in Jerusalem wouldn’t have worked. The kind of argument that would be taken as a sign of respect in Jerusalem would have been offensive in Tokyo. I found my own Southern upbringing helpful in understanding the Japanese perspective: both cultures placed a great emphasis on manners and on not contradicting people in public. So I encouraged the team in Tokyo to be “politely persistent.” Being polite was their preferred way of showing they Cared Personally. Being persistent was the way they were most comfortable challenging Google’s product direction.

I was gratified to see the results. The team in Tokyo became not just persistent but relentless in their campaign to be heard. Thanks in part to their polite persistence, a new product, AdSense for Mobile Applications, was born.

Of course, it isn’t always that simple. If you are a single person in a culture that is unwilling to challenge directly or thinks caring personally is “unprofessional” then it can be daunting to change the culture around you. When I teach Radical Candor, students often say to me, “This is all well and good. I agree with everything you’re saying. But my boss doesn’t operate this way!” When your boss or the culture doesn’t support you, it’s definitely harder. But the good news is that if you are a manager, you can usually create a subculture of Radical Candor on your team. And often the positive benefits to both morale and results are apparent enough it gets copied.

Showing You Care Personally Looks Different in Different Cultures

My friend Astrid Tuminez has a great story about how important it is to adapt the way you show you care to a different cultures.

Astrid grew up in the slums of the Philippines and went on to have a career that spanned Moscow (where I worked with her), New York, and Singapore. While at the US Institute of Peace, she was invited to work on the peace process with the Moro Islamic Liberation Front in the southern Philippines. When she first arrived, she acted like a New Yorker—very business-like, making back-to-back appointments.

Then a member of the Philippine negotiating team told her that someone from the Muslim/Moro group had sent a note to Manila saying, “Who is this woman and what planet is she from?” The person who gave Astrid this feedback was particularly invested in Astrid’s success because they had connected over the fact that they were from the same province. However, Astrid had gone to college and graduate school in the US and had developed American habits and an American affect.

To the Muslims, Astrid had come across as unfeeling, inhospitable, and foreign even though she was Filipino and could speak Filipino. Thinking it over, she realized that she’d made some significant mistakes—such as hosting meetings with people without offering them real food, which was so important in the culture. She spent the next few months listening, and making only “loose” appointments. She attended public events and made the rounds without scheduling people back-to-back. And she made sure she had a lot of food available when she hosted meetings.

By taking time to show she cared about the people she was working with in the way that was expected culturally, she was able to build trust and show she cared deeply about the peace process. Eventually the Moros became very willing to speak to her and to take her places where other outsiders couldn’t or wouldn’t go. It made all the difference in her ability to be effective in the complex and nuanced negotiations her job required.

I met Astrid when we both worked in Moscow, where the cultural norms were very different. I was working for the Soviet Companies Fund. My job was to teach factory directors to write business plans to help attract investment from American pension funds. This was in 1991, just a couple years after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of the Cold War, and we were working with military factories. As you can imagine, there was a good deal of suspicion about these American Kapitalistes coming in to “help.” At first, I was helped by my appearance. I was 23, five feet tall, and female. “Why, we expected a capitalist pig and in comes a little girl!” exclaimed one executive. Luckily, I knew my stuff well enough to earn his respect. By the end of the day, he exclaimed, “Well, now we know you can write a beezneess plan. Now, let’s see if you can drink vodka!”

If I had been back in college at a party, I would have ignored this as a stupid challenge best met by leaving without a sip. But I had been in Russia long enough to know that wasn’t what was happening at all here. He wasn’t challenging me to show how tough I was, he was asking me to earn their trust. I needed to show that I cared about them, and that I was a human being, just like them, not a cold-hearted American. Matching those men shot for shot was the best way I could show I cared personally. I’m of Irish extraction, was raised in the South, and had spent my early twenties in Moscow, so I was a world class drinker, and able to do it.

Of course, if you don’t drink, you don’t have to drink just because it’s a cultural norm in order to show you care personally. You just have to be sensitive to the cultural norms and explain your way around them. For example, I once had to do a deal in Islamabad. The negotiation happened over copious amounts of tea and eventually the inevitable happened. I had to use the bathroom. As there was no women’s room in this particular building, this was a cause of some consternation. One man suggested he guard the door, but a more conservative man was clearly profoundly uncomfortable with a woman using the restroom. Instead, he proposed a bucket in a mop closet. That was where my cultural sensitivity ended. However, I didn’t want to push him to a place where he was uncomfortable. I suggested I drive back to the hotel, use the facilities there, and then return. I figured he’d opt to let me use the restroom rather than wait an hour for me. However, he was happy to wait.

So again, Radical Candor can be applied across all cultures, but it may look very different from one culture to the next. I’ve led teams all over the world and have seen firsthand that it’s possible to adapt Radical Candor equally well for Jerusalem, Tokyo, Moscow and everywhere else I’ve worked.

One of the best things you can do to understand how to adjust for different people and different cultures is to be clear about your intentions for Radical Candor and then to ask people to gauge your interactions. Knowing how someone perceived an interaction with respect to how you perceived it will help you adjust in the future.

Do you have any stories to share about adjusting your communication style for different cultures? Let us know about how you handle Radical Candor and cultural differences.

—–

Adapted from an excerpt from Radical Candor: Be a Kickass Boss Without Losing Your Humanity. Order the book here.